What young Europeans want EUrope to do

At first sight, the relationship between Europeans and their right to free movement appears straightforward. As laid out in the previous chapter, Europeans support free movement within the European Union, be it for themselves or for others. Broadly speaking, they are equally supportive of the right to settle in other countries within the European Union as they are of the right to cross borders unimpeded within the Schengen Area. Young Europeans are even more likely than older generations to express these views.

From our 200 qualitative interviews, free movement emerges as the strongest benefit attributed to the EU. When asked about the single most important thing the EU had done for them, an overwhelming 42% of all interviewees cited free movement, like this Romanian researcher born in 1981:

“For me personally I think it is the ability to study, work, live in various parts of Europe, to have a more diverse understanding of what Europe is. That is probably the most wonderful thing that Europe has to offer to its own citizens [...]. I am extremely glad that this came in my life when I could take advantage of it.” 32

Similarly, free travel was the most commonly named formative European moment (16% of all interviewees).33 A French consultant born in 1994, describes it as follows:

“I think it’s something wonderful for us Europeans to be able to travel everywhere […]. There is no bureaucracy, you don’t have administrative problems to travel around and also to work abroad. It’s really easy for us and something very rich for all of us to go and learn abroad from other cultures, to go and visit other countries, to understand why this space exists, what history it has, especially because of all the wars that happened in Europe, and now it’s really different, and it’s a continent that’s really at peace.” 34

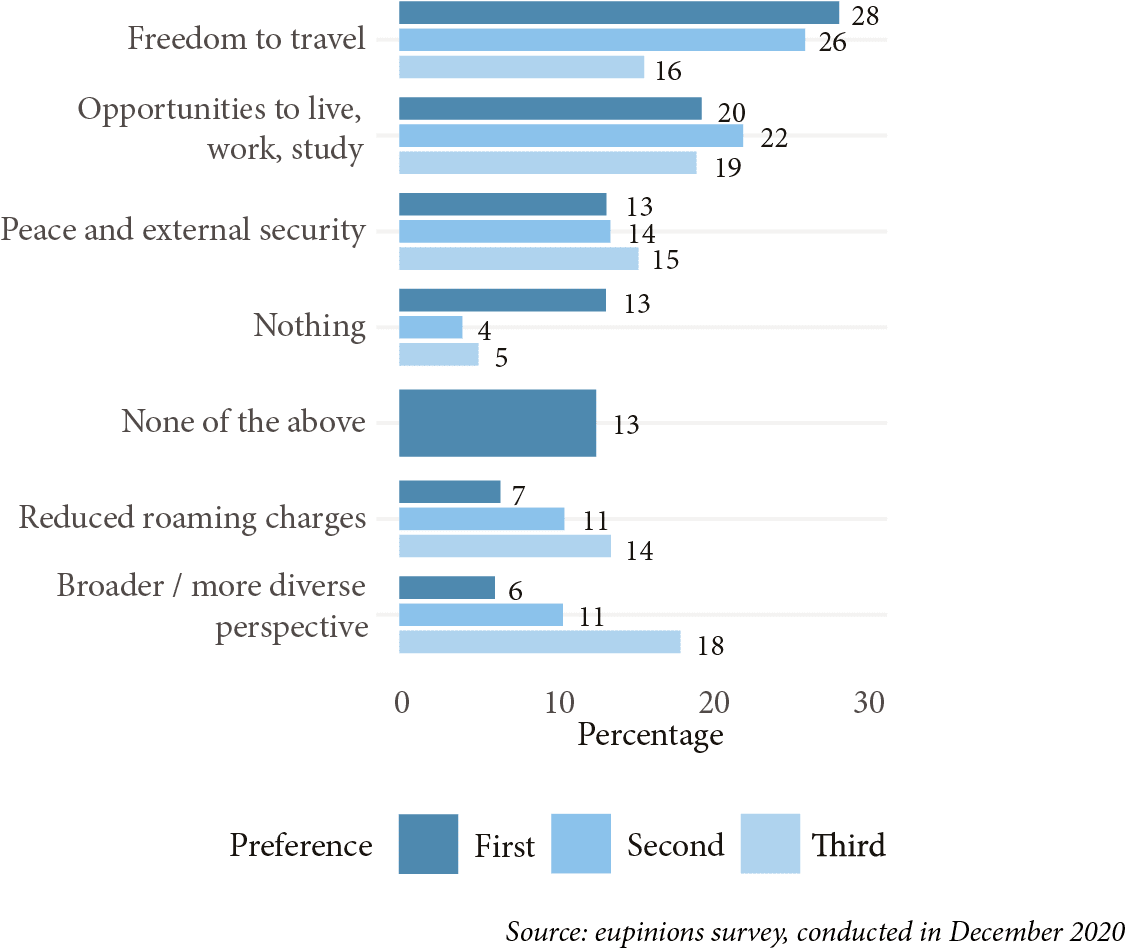

These observations derived from our interviews are no surprise. Our December 2020 opinion polling showed that half of all Europeans view opportunities to work and study abroad as one of the three most important things the EU has done for them personally.35 Further, Eurobarometer surveys have confirmed repeatedly that the vast majority (84%) of EU citizens support the “free movement of EU citizens who can live, work, study and do business anywhere in the EU”.36

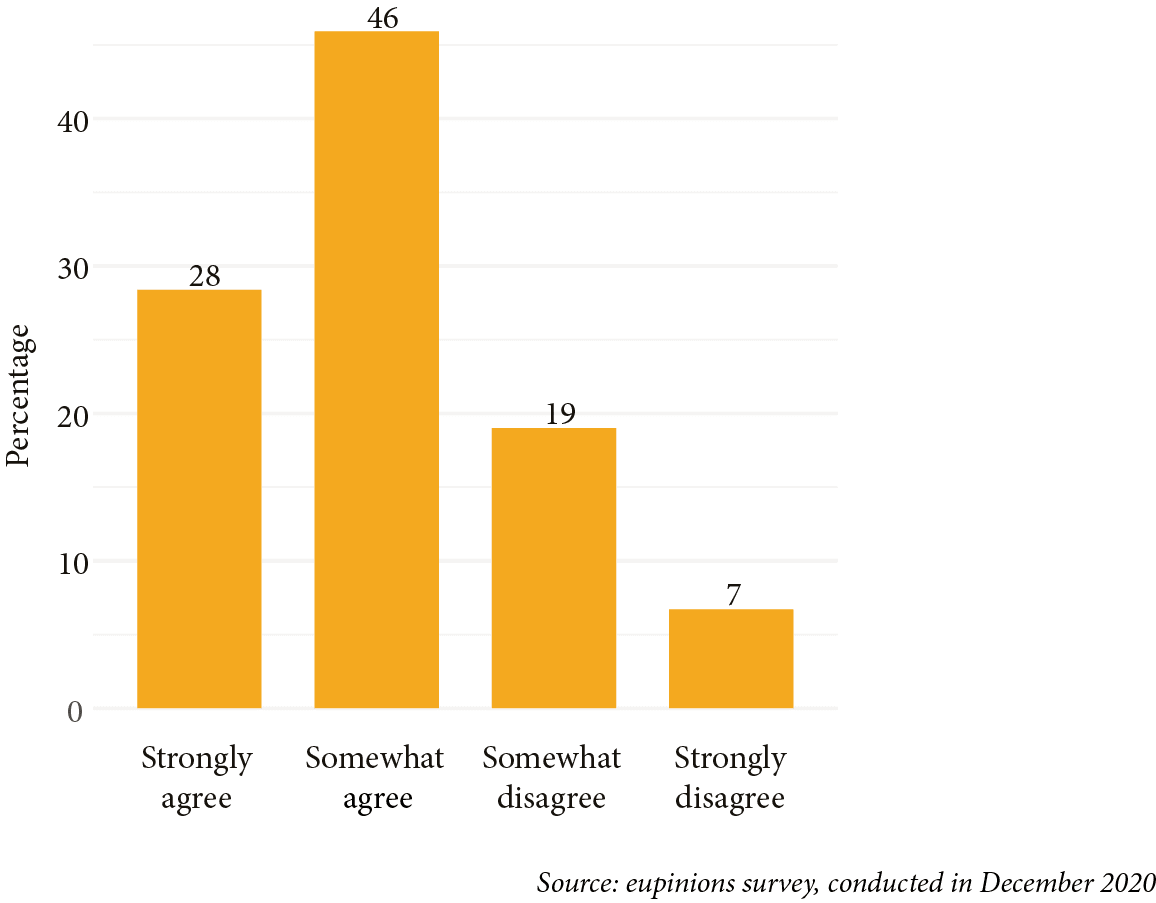

Europeans also value their right to travel unimpededly within the Schengen Area. According to our December 2020 polling, 61% of all European citizens view the right to cross borders within the Schengen Area without undergoing any border checks as one of the three most important things the EU has done for them personally.37 The same proportion agrees that “the Schengen Area has more advantages than disadvantages for them personally.”38 Combined with the finding from our December 2020 polling that nearly three-quarters of Europeans agree that “the EU would not be worth having if it didn’t offer freedom to travel, work and study in other EU member states”, we find that the fundamental legitimacy of the EU is closely intertwined with the rights to free travel and to free movement.39 Further, our December 2020 polling shows the widespread popularity of borderless travel across all age groups, with Europeans aged 15-29 only slightly more likely to mention free travel as one of the top three things the EU has done for them personally (64% compared to 61% overall).40 A quarter of all European citizens also mention the abolition of roaming charges when communicating from abroad as one of the three most important things the EU has done for them personally, which suggests that they have availed themselves of the opportunity to travel within the European Union on a short-term basis.41

Figure 3

If it did not offer the freedom to travel, work, study and live in other EU member states, the European Union would not be worth having

Regarding the right of EU citizens to settle anywhere in the EU, our December 2020 polling showed that 58% of young Europeans chose ‘opportunities to live, work and study abroad’ as one of the top three things the EU has done for them personally, compared to 50.5% of those aged 55+.42 This is confirmed by Eurobarometer polls that found that 89% of European citizens aged between 15-24 support the right of EU citizens to settle anywhere in the EU, up 6 percentage points compared to those over the age of 55.43 This small but significant difference likely reflects the majority of students and apprentices in the younger age bracket and their access to EU programmes such as Erasmus, the European Solidarity Corps or the DiscoverEU scheme. The impact these programmes have had on young people is captured by a Polish secondary school student born in 2001:

“Recently, I was travel[ling], thanks to European Union programme ‘DiscoverEU’, and I visited a lot of museums and I saw the art and how similar the art was […]. Art says a lot about a society, so we had very similar problems in [our] countries: wars about religion and wars about independence and I think that when I saw that, I definitely saw myself as European.” 44

Figure 4

Of the following, what are the most important things the EU has done for you personally? Rank top three in order of importance

According to the same survey, younger Europeans are also more likely than older generations to hold positive views on the immigration of people from other EU member states into their home country.45 78% of those aged 15−24 hold such positive views, compared to 63% of those aged 55 or over. More specifically, when asked whether they are for or against the right of EU citizens to live in other EU countries, a large majority of 15-29-year-olds express their support (81%, compared to 73% overall and 69% of those aged 55 or older).46

Delving deeper, however, it appears that the relationship between Europeans and their right to move freely within the European Union is more complicated than one might think from the polls above. Europeans are generally unaware of the difference between free travel and free movement, and few make use of their right to move freely within Europe, be it temporarily or to settle in a new country. As a Hungarian communications officer born in 1990, put it:

“I think most people do not know what it means to be waiting in a long queue just to get to the other side of a border until they personally experience it. So, the fact that I can move freely, travel freely, and work freely is a true European gift.” 47

Although they greatly value free movement, European citizens have a limited understanding of what it involves. For our interviewees, the ability to travel freely without having to undergo border controls seems to go hand in hand with their exclusive right as EU citizens to work, settle and live in any other EU country, even though these two rights are clearly distinct from a legal point of view. For instance, a young cohesion policy expert and economist from Hungary told us that the most important thing the EU had done for him personally was “free movement [...] travelling without a passport. I think it’s a common answer but it’s because it’s very popular, very useful, one of the biggest aims in our common European history.”48

Talking about the Schengen Area more specifically, fewer than one in two European citizens know what the Schengen Area is. One in three have never heard of it.49 Among those who declare knowing what the Schengen Area is, many do not know whether their country belongs to it (18%) or believe that it is easier to travel outside the Schengen Area than within it (27%). Young Europeans are even less likely than older generations to be aware of the Schengen Area. This may be because most young Europeans were not even born when the original Schengen Agreement was signed in 1985. Hence, it is less surprising that only 30% of European citizens aged between 15 and 24 declare being aware of the existence of the Schengen Area, as opposed to 50% among those aged 25-39 and 52% among those aged 40−54.50

Further, surprisingly few European citizens make use of their right to cross borders for temporary sojourns abroad. In 2018, a Eurobarometer survey found that two in five Europeans had never travelled to other countries within the EU.51 This observation was even more striking in eight EU member states (Greece, Romania, Italy, Portugal, Hungary, Bulgaria, Spain and Poland), where the majority of residents had never entered another EU member state. Among those who travel within the European Union, a tiny minority of 4% would cross an intra-EU border at least once a month, whereas 21% would cross one less than once a year.52

When it comes to permanent settlement, only 3.9% of all those who were born in one of the 27 EU member states had settled in another EU member state as of 2019. This figure is similar to the world’s average of 3.5%. In six member states (Malta, France, Ireland, Spain, Sweden, and Denmark), permanent intra-EU emigration levels are below 2%, while over 10% of those who were born in Croatia, Romania and Luxembourg are now living in another EU member state.53

While Europeans highly value freedom of movement in principle, many do not directly benefit from this right. In our own opinion poll conducted in March 2021, 44% of Europeans stated that they had not personally benefited from free movement.54 Responses to this question revealed a large age difference: only 25% of young Europeans (aged 16-29) disclosed not having benefited from free movement, compared to 59% of those aged 55 or above. In many cases, it is easier for young people to be mobile: they are more likely to be undertaking studies or apprenticeships and are less likely to have set familial and financial commitments, which would make settling in another EU country more complex. In addition to these age-related opportunities, it is now (unless in times of Covid-19) much easier to settle in other European countries than it was when those now aged 55 or over were young. In addition to the most dramatic changes that are the fall of the Berlin Wall and the creation of the Schengen Area, modes of transport between European countries are now much faster and more affordable, offsetting some of the personal costs of relocating abroad.

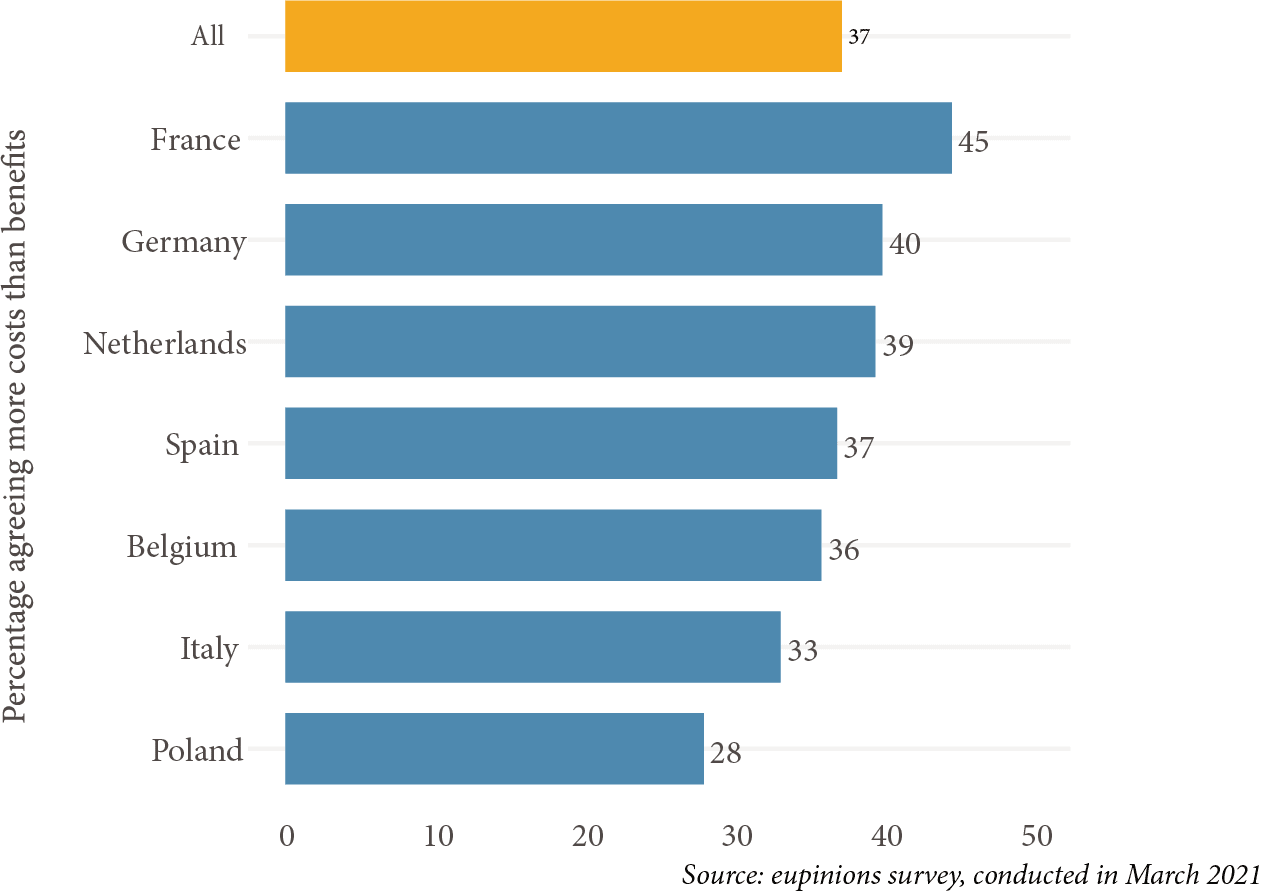

While the large majority of Europeans value free movement for themselves and others on an individual basis, at country level, they are much more divided on whether free movement has more benefits or costs for their country. Our March 2021 polling revealed that 37% of Europeans thought free movement had more costs than benefits for their country, while only 32% felt that the benefits outweighed the costs.55 While 45% of French respondents thought there were more costs than benefits to free movement for France, only 28% of Poles agreed with that statement.

Figure 5

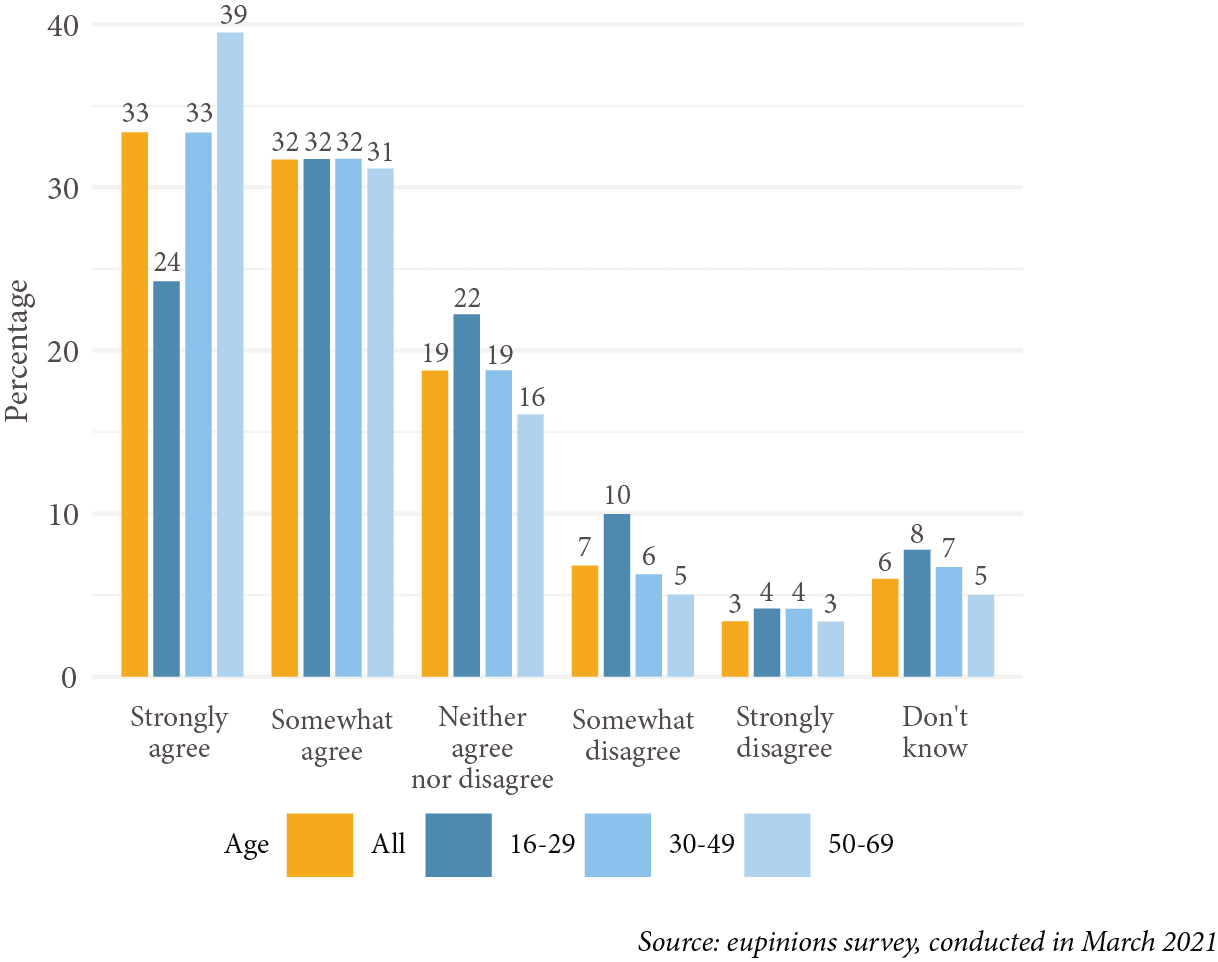

Finally, when asked about EU external border management in our March 2021 polling, nearly two-thirds of Europeans (65%) agree that to have free movement internally, the EU must have well-guarded external borders.56 This confirms earlier findings showing that 68% of all Europeans favour a reinforcement of EU external borders with more European border guards and coastguards.57 As can be seen in Figure 4, young Europeans are slightly more divided than their parents on this matter. Our March 2021 polling found that only 55% of young Europeans aged between 16 and 29 think that well-guarded borders are a prerequisite to free movement within the European Union, which reflects earlier findings showing that 58% of Europeans aged 15-24 support the reinforcement of EU external borders.58

Cooperation among EU member states on border management, however, does not necessarily mean restrictive immigration policies. A majority (54%) of young Europeans view the immigration of people from outside the EU positively. In particular, 73% of young Europeans believe that their country should help refugees.59

Figure 6

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement? “To ensure freedom of movement inside the European Union, the EU must have a well-guarded external border”

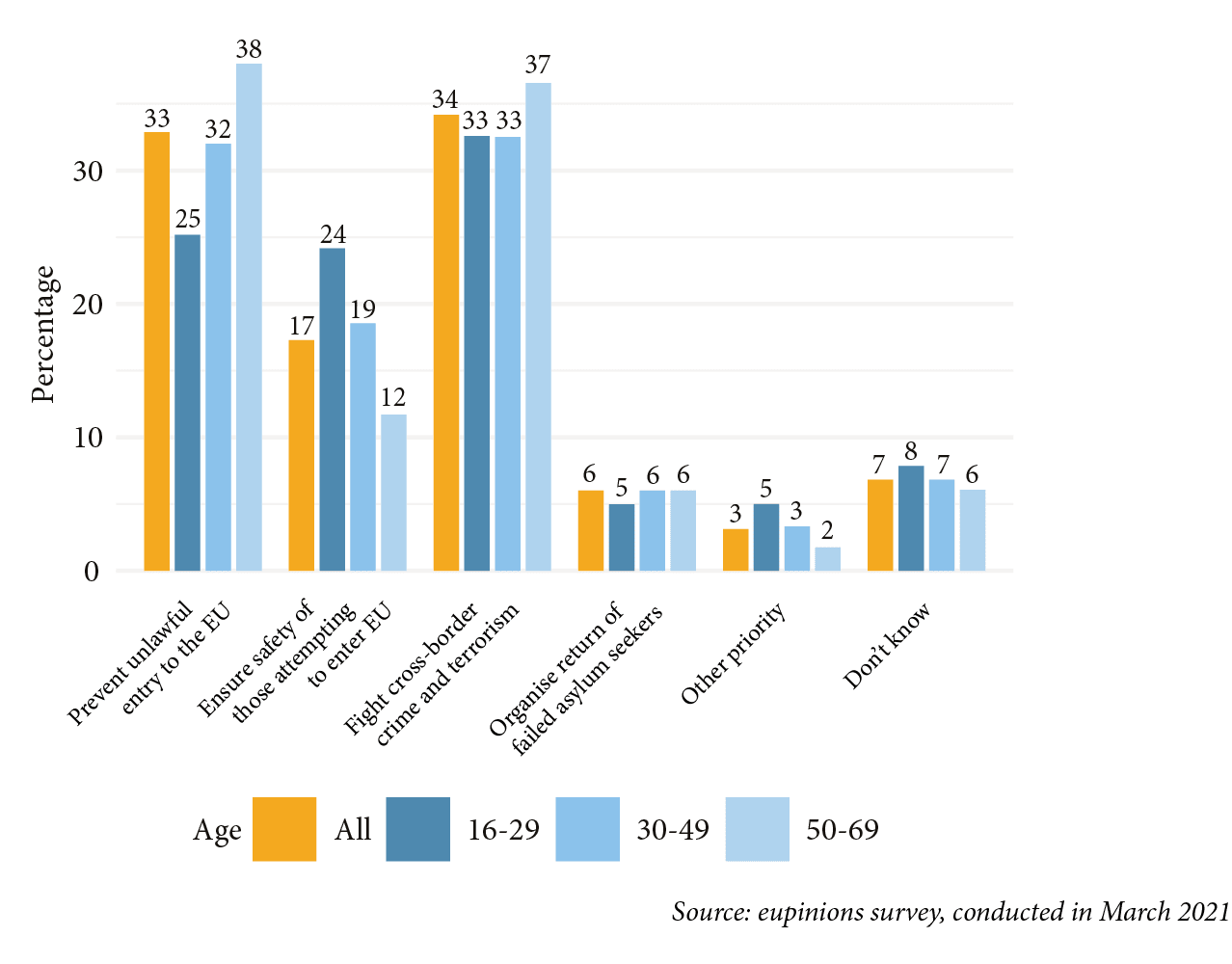

According to our March 2021 polling, only 25% of Europeans aged between 16 and 29 believe that the top priority of Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, should be to prevent unlawful entries into the European Union.60 In contrast, younger and older Europeans are united in the belief that the top priority of European border guards should be the fight against cross-border crime and terrorism. 17% of the population even consider the top priority of European border guards to be the safety of those attempting to enter the European Union, with one quarter of young Europeans sharing this opinion.61

“I think one really, really important issue that needs to be solved by 2030—but I’d rather have it solved by next year or tomorrow, if we could—is a humane asylum and migration system, because I think it’s a shame that people are still dying every single day in the Mediterranean sea...it’s a big EU failure...and we not only fail those people who are in need, but we also fail each other...there is no solidarity.” 62

Figure 7

The European Union is currently recruiting 10,000 European border guards to be deployed at the external borders of the European Union by 2027. In your opinion, what should be their top priority?

Opinions like the above one by a German master’s student born in 1996 were likely influenced by the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’, mentioned by several of our interviewees as the worst moment in recent European history. An Italian business development coordinator, stated that “[t]his crisis brought to light many structural weaknesses within the European system. It was not able to manage the crisis.”63 Like a student from Austria born in 1995, who acknowledges that “you don’t feel at home [anywhere in the EU] if you don’t have the rights”, several of our interviewees expressed the wish for the EU to step up its solidarity with member states at the fringes of Europe and expand the full rights of free movement to newcomers from third countries.64

What the EU is and is not doing

Public opinion on free movement directly corresponds to the actions of the European Union and its predecessors. Europeans greatly value free movement, a policy that European governments have been developing for over seven decades. In turn, Europeans show an appetite for well-guarded external borders, which has been the focus of European efforts in recent years.

The right to free movement for EU citizens has been an enduring commitment of the EU and its predecessors. As early as 1957, the Treaty of Rome first introduced the freedom for workers to settle anywhere within the Community to seek employment. At that stage, free movement for workers was conceived as a means towards the achievement of a greater end: a common market. As the European Economic Community was being established, it was necessary to ensure that labour, as a means of production, could move freely within the community.

It was only a decade later, in 1968, that family members of workers were also allowed to move freely within the European Economic Community.65 Another 22 years later, the European Council adopted three directives expanding the right to free movement to all the citizens of member states, provided they have sufficient resources to sustain themselves and have secured health insurance.66

Progressively moving away from the original economic conception of the right to free movement, the 1992 Maastricht Treaty first recognised the unconditional right of all citizens of member states to settle permanently in any member state, regardless of their occupation status.67 In a final move towards the recognition of free movement as an individual freedom, Article 45 of the 2002 EU Charter of Fundamental Rights provides that “every citizen of the Union has the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the member states.” In accordance with this new conception of free movement, the European Parliament and Council lifted the provisions that required those who moved within the European Union to have sufficient resources and health insurance, an exception being made for inactive citizens.68

As a significant addition to the right of EU citizens to settle in other member states, European governments facilitated the mobility of its people by adopting the 1985 Schengen Agreement and the subsequent 1990 Schengen Convention, thereby creating a single jurisdiction for international travel purposes. This meant, in practice, the abolition of internal borders among the contracting parties and the adoption of a single entry visa policy with regards to third country nationals. From five original signatories in 1985, the Schengen Area now counts 26 European countries, 22 of which belong to the European Union. Nationals of all parties can, under normal circumstances, cross internal borders without undergoing any checks.

One must differentiate between the right to freely cross borders within the Schengen Area and the right of EU citizens to settle in other countries. For instance, nationals from Schengen countries can enter Switzerland unimpeded but need to obtain a residence permit if they intend to settle. In turn, EU nationals can settle in Bulgaria, but will face border controls. The Schengen Area has equivalents worldwide, such as the ECOWAS area in Western Africa or the Commonwealth of Independent States in Central Asia. The right to free movement for EU citizens, on the contrary, is unrivalled.

While the right to freely cross borders within the Schengen Area and the right of EU citizens to settle in any EU country are distinct, they reinforce one another. Settling in another country than the one of your birth is inevitably easier if you can seamlessly travel back and forth between your country of origin and your country of settlement. To that extent, the Schengen Area is part of countless administrative barriers faced by those who exercise their right to settle in a new country, ranging from the transferability of pensions rights to the recognition of professional qualifications. Every year, the Euro Direct Contact Centre receives many thousands of queries by EU citizens highlighting outstanding administrative barriers to free movement.69 Taking these queries into account, the European Parliament and Council have agreed on a wide range of policies that aim to remove barriers to free movement within the EU. The 2010 EU Citizenship report flagged 25 issues faced by mobile EU citizens, including issues related to the recognition and access of civil status documents or taxation problems when registering cars.70 As a result, it seems fair to conclude that free movement has now become an end in itself: enormous efforts are being put in to achieve it. Tellingly, 59% of all Europeans consider the right to free movement as one of the two greatest achievements of the European Union.71

Freedom of movement is a right that the EU distributes, and which favours a selection of privileged individuals only. The full right to free movement can only be enjoyed by Europeans who hold the citizenship of a member state of the EU, and hence European citizenship. The extent to which EU residents can enjoy certain aspects of free movement is governed by national legislation and depends on how long a person has been resident in an EU member state and whether they fulfil a set of nationally defined preconditions, such as proof of sufficient income, valid insurance and ‘level of integration’ in the host community.72 On a spectrum of high to low access to aspects of free movement, third country nationals who are long- term residents in an EU member state, highly skilled workers, researchers and students are at the top end.73 This means that if a third country national of one of these groups wishes to move to another EU member state than the one they are currently residing in for more than three months, they have to apply for a new residency permit in that second state. Moving down the spectrum, there are no EU legislative provisions for third country nationals who do not belong to any of the four groups mentioned. Their immigration to an EU member state is governed by national legislation and there are no provisions at EU level that grant them access to anything resembling free movement. At the bottom end of the spectrum are those who cannot even enjoy free movement in the member state they are residing in, such as asylum seekers, who are required to stay within city boundaries while awaiting the outcome of their asylum application.74

The shared management of the external borders of the European Union is widely understood as the “necessary corollary to the free movement of persons within the European Union”.75 The abolition of borders within the Schengen Area means that, theoretically, anyone who crosses the external border can then circulate freely across countries without undergoing further border checks. For instance, someone entering the Schengen Area by crossing the land border between Poland and Ukraine can reach as far as Portugal unimpeded. With the 1985 Schengen Agreement was born the paradox of “Fortress Europe”, a mixture of freedom and security that led to the establishment of Europol in 1994 and of Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, in 2004. The European Parliament and Council deemed it unfair to leave some countries to manage their own segments of the external land border of the Schengen Area (in the example above, Poland) if such management benefited all other countries, including those not guarding any segment of external land border (in the example above, Portugal). Additionally, the European Parliament and Council established Frontex to make sure that Member States could trust and oversee one another in the management of external borders, especially in the context of the enlargement of the EU to ten new Member States in 2004. Indeed, “the Schengen Area’s external border is only as strong as its weakest link”, so it is in the interest of every member state that borders are managed according to shared standards.76

Originally established as a platform for the monitoring of the situation at the external borders of the European Union, Frontex is now a prominent agency. In accordance with its mandate adopted in late 2019, Frontex is set to become the second largest body of the European Union by 2027. The agency is now purchasing its own assets and recruiting a 10,000-strong Standing Corps, the EU’s first uniformed and armed law enforcement service. In line with its new mandate, Frontex is also now operating outside the European Union and developing the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) and the Entry-Exit System (EES) that will track all non-EU citizens’ entry into and exit out of the Schengen Area. After a period during which efforts of the European Union were directed towards the abolition of all sorts of barriers to the free circulation of EU nationals in Europe, the past 15 years have mostly been dedicated to the reinforcement of cooperation among member states at the external borders of the European Union. This trend has reached its peak with the heralding of Frontex as a major actor in border management in Europe, and the development of the agency will remain at the heart of debates on European integration at least until it reaches its full capacity in 2027.

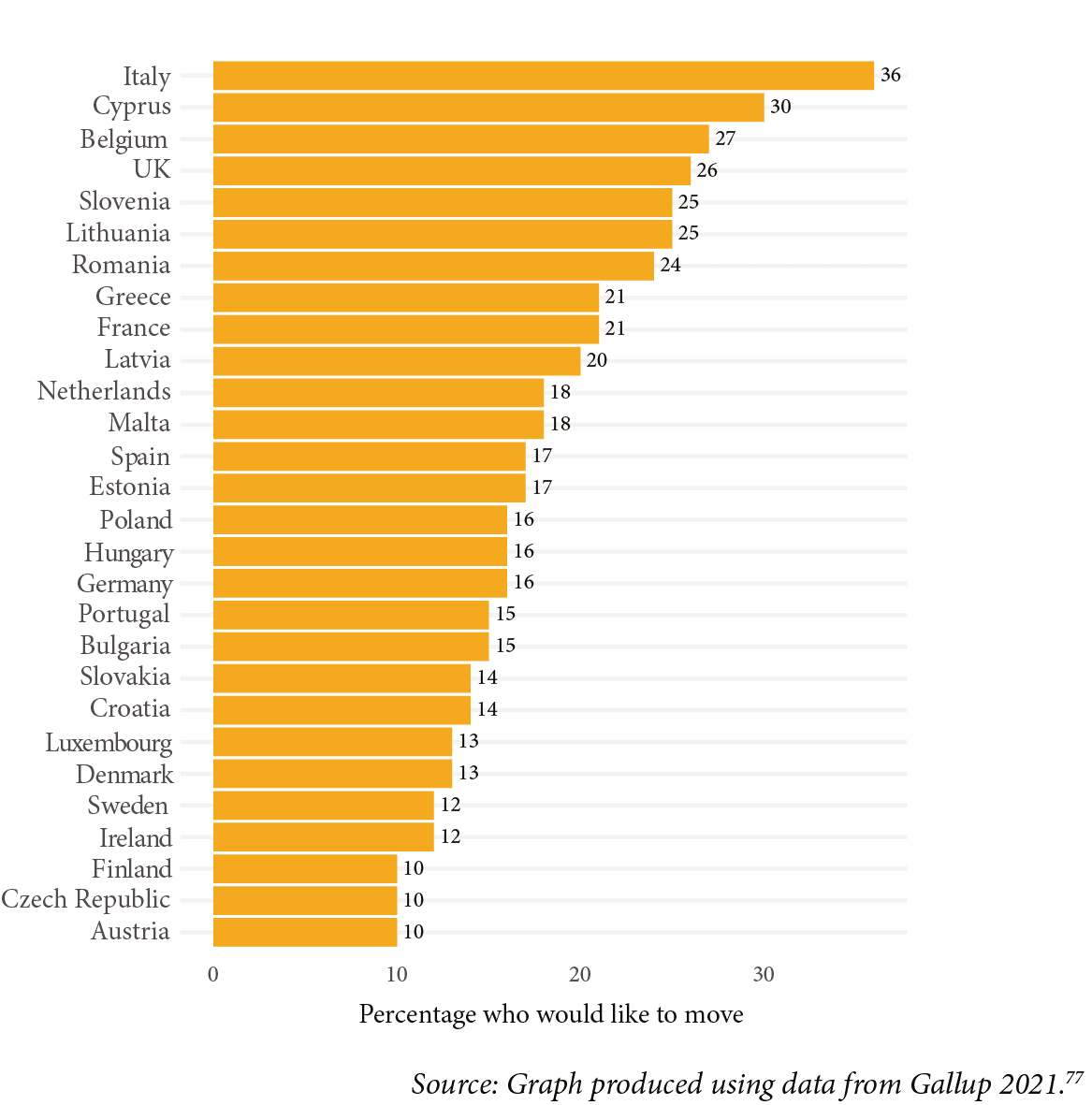

Figure 8

Ideally, if you had the opportunity, would you like to move PERMANENTLY to another country, or would you prefer to continue living in this country? 77

While it is assumed that European citizens can now circulate freely within the bloc and while minds are focused on external borders, a large majority of the EU population remains immobile. According to a 2017 survey, 21% of all European citizens declare that “ideally, if [they] had the opportunity”, they “would like to move permanently to another country.”78 This represents one of the highest values worldwide, the world’s average sitting at 15% as of 2017. This percentage also exceeds 2017 values from comparable states such as Russia (17%), the US (16%), Australia (11%) and Canada (10%).79 The 21% of European citizens aspiring to migrate represented over 100 million people across the then 28 member states of the European Union. Italy was the country where migration aspirations were highest, with an estimated 36% of migration aspirants among the Italian population, followed by Cyprus (30%) and Belgium (27%). At the other extreme, only 10% of the Austrian, Finnish, and Czech populations aspired to migrate as of 2017.80

The proportion of young Europeans who aspire to migrate is particularly high. According to this same survey, a third of all European citizens aged between 15 and 29 would like to change their country of residence. This is a much higher proportion than for those aged 30 to 49 (23%) and for those aged over 50 (13%). Undeniably, European youth drives migration aspirations in the EU. These observations suggest a strong age effect in aspirations to migrate. Across the world, young people are more likely to want to migrate, and Europeans are no exception.81 High migration aspirations among young Europeans do not seem to evidently result from their entitlement to migrate, even if just within the EU. The unavailability of data prior to 2007, however, makes it difficult to assess whether efforts to facilitate migration within the European Union could have resulted in a period effect that could have explained, at least in part, high levels of migration aspirations among young Europeans. Would Europeans who were in their twenties in the 1970s and 1980s have had similarly high aspirations to migrate?

Until now, the European Union has conceived free movement as a negative freedom, focusing its actions on the removal of all sorts of barriers to free movement. However, we suggest that free movement should be understood as a positive freedom: individuals need support to help them realise their migration aspirations. Put differently, “the absence of formal restrictions on movement of people across or within borders does not in itself make people free to move,”82 Various examples of governments worldwide taking action to actively support their nationals who want to emigrate point to the fact that some active support helps individuals realise their migration aspirations. They include most notably the Filipino government with its pre-departure orientation seminars,83 or the Chinese government with its “Going West” campaign, (though possibly for objectives other than helping their citizens realise their positive freedom to migrate).84 When it comes to the EU actively supporting intra-EU settlements, however, European authorities leave a vacuum that is usually filled by private actors, such as for-profit consultants, migration entrepreneurs, trade unions, churches or charities.

Across the EU, migration aspirations have remained fairly stable since 2007, but so has the age gap in relation to it: in 2017, 33% of those aged 15-29 wanted to permanently move to another country, compared to 13% of those aged 50+.85 To address these unfulfilled migration aspirations, the European Union needs to develop more mechanisms to support the long-term settlement of Europeans who want to migrate abroad. While migration aspirations often result from dissatisfaction with some areas of one’s life, someone’s inability to fulfil their migration dream could result in long-term discontent and disapproval of European policies with regard to free movement. Existing schemes, such as the Erasmus programme, the European Solidarity Corps or the DiscoverEU programme are all steps in the right direction but they focus on short-term mobility. Going further in this direction, the European Union should support those of its citizens and residents who aspire to migrate more permanently, in a variety of ways.

What we think the EU should do

We want the EU to promote and widen access to EU-wide schemes that already encourage free movement, such as Erasmus, DiscoverEU and the European Solidarity Corps. Both our opinion polling and our qualitative interviews have demonstrated how transformative the experience of travelling and living abroad, especially during people’s formative years in the late teens and early twenties, is for a sense of shared European identity. The EU should continue to develop and increase funding for the hugely popular Erasmus scheme and make it more visible to young people in areas where few people take part in the scheme. Research has shown that whether or not university students embark on Erasmus exchanges does not only depend on disadvantageous individual characteristics, but largely also on the institution in question and the subject of study.86 The EU should invest in liaising directly with higher education institutions to promote the scheme at Colleges and universities with a high proportion of disadvantaged students, while offering substantive additional financial support for those who lack the means to prepare for and embark on the Erasmus programme. Additionally, the educational benefits of participation in the Erasmus scheme should be made more tangible, through a stronger obligation of home institutions to recognise studies and training completed during people’s time abroad.

Similarly, following from our overwhelming findings of free travel as a formative European experience, the EU should resume the growth of the DiscoverEU scheme, with a higher budget for making the experience accessible to a larger number of young Europeans. As a non-educational programme, DiscoverEU can arguably have the most resonance among young people from a variety of backgrounds and give them the opportunity to experience Europe on a personal level, no matter their academic attainment, which can be shared as a generationally formative moment with their peers across Europe. Practically, this involves lowering the minimum age to participate in the scheme from 18 to 16, so as not to exclude those who leave school after ten years of schooling and are already in vocational training or jobs by the time they are eligible to participate in the DiscoverEU programme. The European Solidarity Corps is another useful programme to enable young people who want to go abroad and gain work experience for their resumé, but relatively few young Europeans know about it. Hence, the EU should increase the programme’s visibility to that of the Erasmus programme and involve more organisations in offering placements. Naturally, this means revoking the discontinuation of traineeships and jobs from 2022 onwards as part of the European Solidarity Corps scheme. This two-way learning experience of having young people work in communities or charitable projects abroad is a great way to foster mutual understanding across Europe and presents an opportunity the EU cannot miss.

We want the EU to address East−West and North−South imbalances within Europe when it comes to freedom of movement. As Eurobarometer data has shown, there are vast country-level differences in who makes use of their right to free movement. Rather than being an ‘elite universities only’ scheme, Erasmus should give incentives to students from West and North European universities to study at institutions in Eastern and Southern Europe. In addition to offering a wider range of courses run in English in non-English-speaking parts of Europe, Eastern European languages should be taught in schools to a similar extent that Western European languages are taught across Europe. While there certainly are labour market reasons why many students wish to learn English, French or Spanish, solely offering those options as second and third languages only solidifies the gap between those countries belonging to the European core versus the European periphery. Of course, national school curricula are outside the EU’s competency, but the EU is not only its institutions, but also the union of its member states. The EU should thus open up the conversation about the possible benefits of widening foreign language learning options in schools in member states. Additionally, making local language classes a firm part of any Erasmus preparation and stay would enhance the cross-cultural experience for young Europeans and allow them to engage with their host communities in a more meaningful way. The EU could also establish incentives within the DiscoverEU scheme to make Eastern Europe more attractive to participants, such as extending periods of validity for tickets in the region, assistance to develop sightseeing programmes or the organisation of events and festivals gathering participants.

We want the EU to enable those Europeans who want to migrate to actually do so. As we have shown, a large proportion of EU citizens want to migrate but do not, despite their globally unique entitlement to do so. If migration aspirations are high, but people stay put, their ability to migrate might be hindered. While non-action despite high mobility aspirations does not necessarily mean that people do not migrate because of administrative or other barriers, we ask the EU to investigate and conduct more research into unrealised aspirations for intra-EU migration and to develop ways to address the issues they uncover. Support for people wishing to migrate could include establishing administrative support and information services to help intra- EU migrants with questions around health insurance, pensions and wider financial planning for moving abroad, or offering integration courses for intra-EU migrants, both pre- and post-departure, in major European cities.

We want the EU to extend the right to free movement to third country nationals who are EU residents. The tension between borderless movement on the inside and hard borders on the outside of Europe are apparent both in our own data and wider research. However, free movement does not start and end with the external EU borders. It is a privilege, which is distributed by the EU in an unequal manner. The establishment of free movement is a European hallmark, but instead of complacency, it should foster European integration. Rather than trying to harmonise national legislations of the EU27 on rights of third country nationals taking up residency in a second or third EU member state, granting them the right to free movement after two years, for example, would level the playing field for EU citizens and EU residents, in addition to shortening bureaucratic procedures. Further, for asylum seekers, the prospect of legally being able to migrate to another EU state two years after being granted asylum would only be in accord with the wider efforts made by the European Union to facilitate the mobility of EU citizens.

Enabling free movement within the European Union requires extensive efforts to remove the true spirit of the European project, but might even result in fewer irregular and dangerous secondary movements. Lastly, offering freedom of movement to EU residents could actually strengthen the argument for EU citizenship, rather than weaken it. Long-term residents would not feel as compelled to naturalise for the sole instrumental purpose of gaining the right to freedom of movement; rather, the desire to acquire citizenship would come from association with the community and a feeling of belonging in the chosen country of residence.

As we have shown throughout this chapter, young Europeans highly value freedom of movement. While we are strong proponents of the right, there are still many Europeans who do not approve of free movement, and even more who have not personally benefited from it. We acknowledge those concerns and wish to close by saying that our call for the extension of free movement is not meant as a normative compulsion that all Europeans should lead more mobile lifestyles. On the contrary, it is precisely because so many have not benefited from it that we call for freedom of movement to be made more accessible to all Europeans, rural, urban, East and West.

32 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Stefan Cibian", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/stefan. ↩

33 In this chapter, 'free movement' refers to the right of EU citizens to settle in the EU member state of their choice, whereas 'free travel' refers to the right to cross borders without undergoing border checks within the Schengen Area. ↩

34 Europe's Stories, "Interview with François d'Andigné", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/francois. ↩

35 Garton Ash et al., 26 Jan 2021. ↩

36 Directorate-General for Communication, "Standard Eurobarometer 93: Europeans' opinions about the European Union's priorities", European Commission, Summer 2020, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2262. ↩

37 Garton Ash et al., 26 Jan 2021. ↩

38 Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, "Special Eurobarometer 747: The Schengen Area", European Commission, Dec 2018, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/26ce02a6-e890-11e8-b690-01aa75ed71a1. ↩

39 Garton Ash et al., 26 Jan 2021. See also: Marie De Somer, "Schengen: Quo Vadis?", European Journal of Migration and Law 22, no. 2 (2020): 178-197. ↩

40 Garton Ash et al., 26 Jan 2021. ↩

41 Ibid. ↩

42 Ibid. ↩

43 Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, "Standard Eurobarometer 93: Europeans' opinions about the European Union's priorities", 2020. ↩

44 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Maria Pancewicz", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/maria. ↩

45 Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, "Standard Eurobarometer 93: Europeans' opinions about the European Union's priorities", 2020. ↩

46 Ibid. ↩

47 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Diana Zsoldos", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/diana. ↩

48 Europe's Stories, "Interview with János Kele", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/janos. ↩

49 Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, "Special Eurobarometer 747: The Schengen Area", 2018. ↩

50 Ibid. ↩

51 Ibid. ↩

52 Ibid. ↩

53 UNDP, 2020, "International migrant stock" database, available at https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp and World Bank, 2020, "Population, total" database, available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL. ↩

54 Garton Ash et al., 25 May 2021. ↩

55 Ibid. ↩

56 Ibid. ↩

57 Directorate-General for Communication, "Standard Eurobarometer 92: Public opinion in the European Union", European Commission, Autumn 2019, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2255. ↩

58 Ibid. ↩

59 Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, "Standard Eurobarometer 93: Europeans' opinions about the European Union's priorities", 2020. ↩

60 Garton Ash et al., 25 May 2021. ↩

61 Ibid. ↩

62 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Lilly Schreiter", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/lilly. ↩

63 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Matilde Bottazzoli", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/matilde. ↩

64 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Evelyn Shi", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/evelyn. ↩

65 Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 of the Council of 15 October 1968 on freedom of movement for workers within the Community, now replaced by Regulation (EU) No 492/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2011 on freedom of movement for workers within the Union. ↩

66 Council Directive 90/364/EEC of 28 June 1990 on the right of residence, Council Directive 90/365/EEC of 28 June 1990 on the right of residence for employees and self-employed persons who have ceased their occupational activity, and Council Directive 90/366/EEC of 28 June 1990 on the right of residence for students. ↩

67 Article 21 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. ↩

68 Directive2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the member states. ↩

69 Directorate-General for Communication, "Europe Direct Contact Centre: Annual Activity Report 2019", European Commission, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/edcc_annual_activity_report_2019.pdf. ↩

70 European Commission,"EU citizenship report 2010: Dismantling the obstacles to EU citizens' rights", European Commission, 2010, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0603:FIN:EN:PDF. ↩

71 Directorate-General for Communication, "Standard Eurobarometer 93: European citizenship", European Commission, Summer 2020, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2262. ↩

72 Justyna Bazylińska-Nagler, "Free-Movement Rights of Third Country Nationals in the EU Internal Market", Wroclaw Review of Law, Administration & Economics 8, no.1, 2019: 27-43, https://doi.org/10.1515/wrlae-2018-0022. ↩

73 European Commission, "Migration and Home Affairs, EMN Glossary: right to free movement", 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/glossary_search/right-free-movement_en. ↩

74 IvAF-Netzwerk BLEIBdran. Berufliche Perspektiven für Flüchtlinge in Thüringen, "Residenzpflicht, Wohnsitzauflage, Wohnsitzregelgung", May 2020, https://www.fluechtlingsrat-thr.de/sites/fluechtlingsrat/files/pdf/Projekte/202005Residenzpflicht_Wohnsitzauflage_Wohnsitzregelung.pdf. ↩

75 Council Regulation (EC) No 2007/2004 of 26 October 2004 establishing a European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union; Regulation (EU) 2016/1624 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2016 on the European Border and Coast Guard; and Regulation (EU) 2019/1896 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 November 2019 on the European Border and Coast Guard. ↩

76 Frontex, "Roles & Responsibilities", Frontex, 2021, https://frontex.europa.eu/we-support/roles-responsibilities/. ↩

77 Gallup World Poll, "Move permanently to another country", World Poll Survey, 2021, aggregate values. ↩

78 Ibid. ↩

79 Ibid. ↩

80 Recorded in 2017, the observation that Europeans want to migrate appears to remain valid as of 2020. The absence of data in some EU member states for the years 2018 to 2020, however, makes reliable comparisons impossible. It also remains to be seen what impact the Covid-19 pandemic will have on migration aspirations in Europe. ↩

81 Silvia Migali and Marco Scipioni, "Who's about to leave? A global Survey of Aspirations and Intentions to Migrate", International Migration 57, no. 5 (2019): 181-200, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/imig.12617. ↩

82 Jeni Klugman, "Human Development Report 2009: Overcoming Barriers – Human mobility and development", UNDP-HDRO, 2009, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2294688. ↩

83 Commission on Filipinos Overseas, "Home", Office of the President of the Philippines, 2019, https://cfo.gov.ph/. ↩

84 See Emily T. Yeh and Elizabeth Wharton, "Going West and going out: Discourses, migrants, and models in Chinese development", Eurasian Geography and Economics 57, no. 3 (2016): 286-315, https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2016.1235982. ↩

85 Gallup World Poll, "Move permanently to another country", World Poll Survey, 2021, values by age groups. ↩

86 Sylke V. Schnepf and Marco Colagrossi, "Is Unequal Uptake of Erasmus Mobility Really Only Due to Students' Choices? The Role of Selection into Universities and Fields of Study", Journal of European Social Policy 30, no. 4, October 2020: 436-51, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0958928719899339. ↩