What young Europeans want EUrope to do

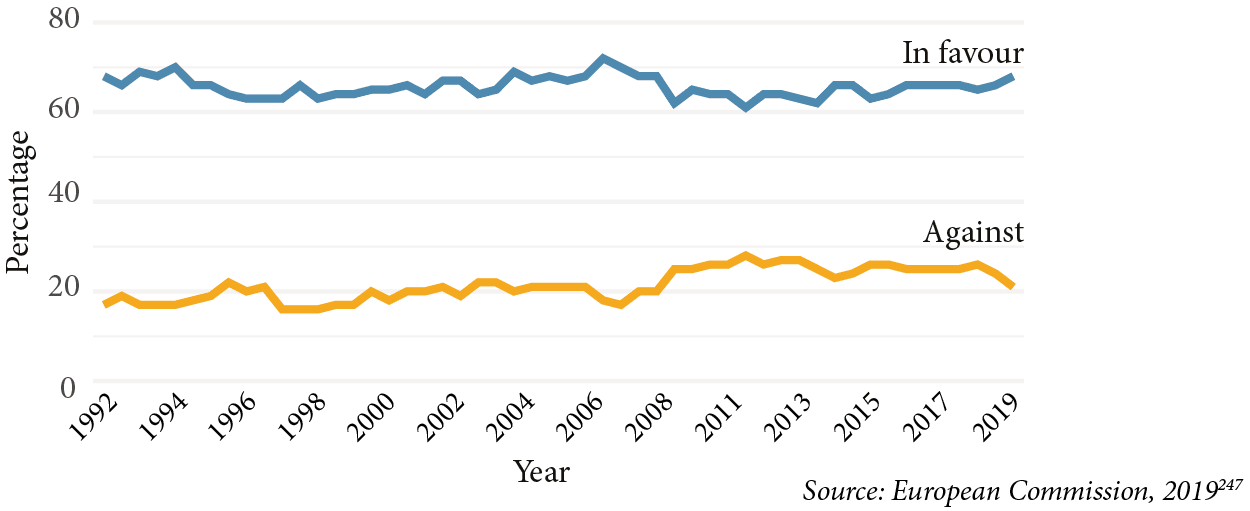

When it comes to common external action, younger and older Europeans alike favour stronger European cooperation—but the devil is in the detail. Support for a common foreign policy has remarkably remained constant across time and across age groups, suggesting that there are no major age, period or cohort effects at play (Figure 22).

The idea of a common EU foreign policy has remained strikingly popular throughout continued enlargement rounds (EU12, EU15, EU27, EU28), 9/11, the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, the financial crisis, US strategic rebalancing, and the latest populist and isolationist trends. There is, however, some evidence of an age or cohort effect when it comes to enlargement: while in 2019 the average support for extending EU membership to other countries was around 44%, 60% of young Europeans aged 15-24 were in favour.246

Figure 22

What is your opinion on each of the following statements? Please tell me for each statement whether you are for it or against it. "A common foreign policy of the 28 member states of the EU (% - EU)" 247

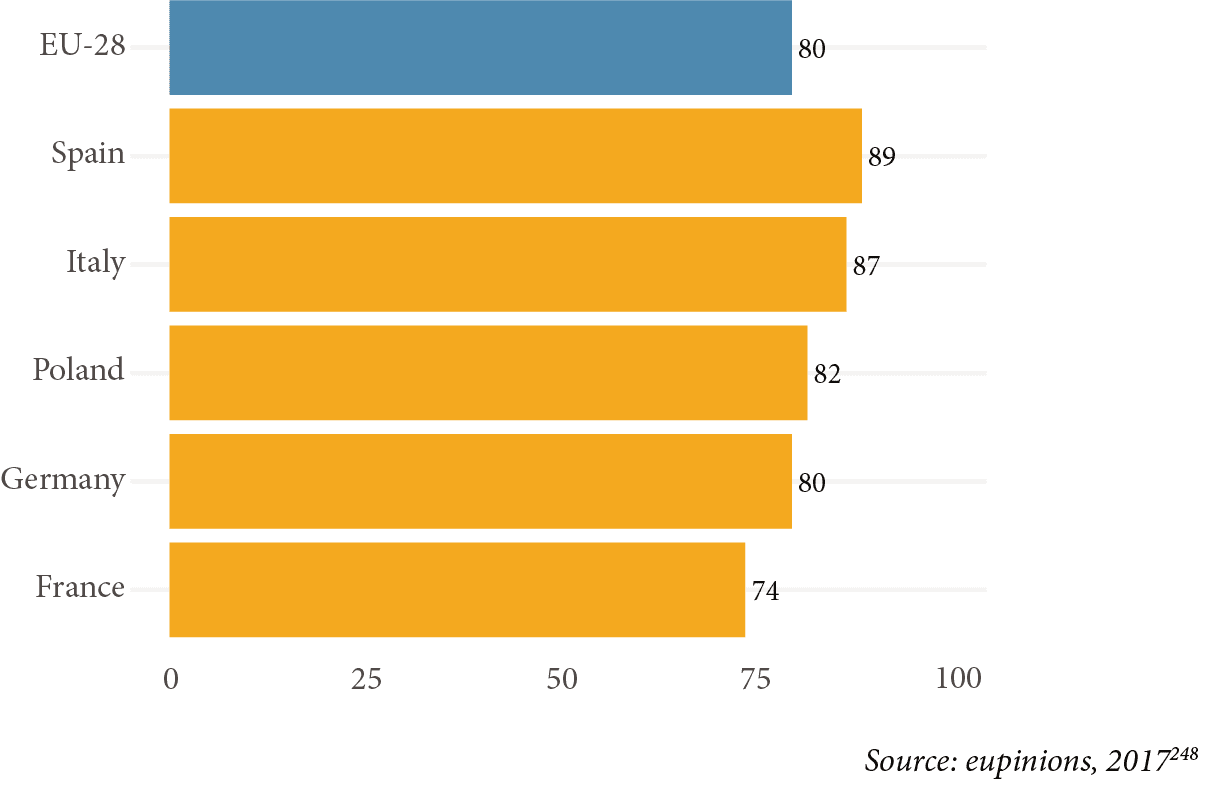

Figure 23

Even though some countries are more supportive of a common foreign policy than others—only a small majority in Ireland, the UK, Finland and Sweden, but over 75% in France, Germany, Benelux, Visegrád and Baltic countries—most Europeans favour more coherent European foreign policy.

The qualitative interviews we carried out reflect widespread support for a common EU foreign policy and a more assertive Union on the global stage. David Gill, Consulate General at the German Consulate in New York, stated that he would like to see “Europe as a strong, self-confident, determined entity in world policy.”249 Similarly, Sylvie Kauffmann, editorial director of Le Monde, told us: “one thing I would really like the European Union to progress towards is to have a common foreign policy.”250 Robert Grzeszczak, professor of European Law at the University of Warsaw, adds that “the goal for us, for the future in ten years, is to create a real foreign policy. The (unified) foreign policy will be a signal for other states that the European Union really is a Union.”251 Not only do most EU citizens support a common foreign policy, but they also agree that the EU should strive to play a much more influential role in global affairs (Figure 23).

But while a more influential EU on the global stage is desirable in theory, it is not always a priority—particularly among the younger generations. The top five priorities listed by young Europeans (aged 15-30) include fighting climate change (67%), improving education and training (56%), fighting poverty as well as economic and social inequalities (56%), creating jobs (49%) and improving health and well-being (44%). Only 28% of young Europeans seem to think that ensuring the EU’s security and defence should be a paramount concern (see Figure 14 p52).252

Most EU citizens tend to agree that the EU is a place of stability in a troubled world, even though there is variation across the EU27. Though the overwhelming majority of respondents in Portugal, Luxembourg and Denmark find the EU to be a stabilising force (87%, 82% and 81% respectively), only 56% of Italian and Czech citizens do so.253 As we have seen, when asked to name the most important thing that the EU has done for them, young Europeans rank freedom of travel as the most significant contribution, with the freedom to live, work and study in EU states coming in second. Peace and security come third, with only 13% of respondents choosing it as the first option.254

As such, foreign and security policy does not rank among the highest priorities for Europeans—young or old. The different strategic identities and foreign policy cultures across Europe also result in significant disagreement as to what a common European foreign policy would entail in practice. Traditional fractures emerge as soon as more tangible aspects are considered, including non-secondary issues such as the aims of a common foreign and security policy (e.g. operational capabilities, decision-making structures or industrial cooperation in the field of defence). Interventionist member states find themselves at odds with neutral countries such as Ireland or Austria, Atlanticist Baltic countries consider French moves for greater strategic autonomy as threatening to Nato, and smaller member states fear cooperation between larger member states’ defence industries.

Diverging European stances vis-à-vis third countries—most prominently the US and China—also tend to cripple the EU’s ability to adopt coherent policy positions. When it comes to China, European capitals’ bilateral relations with Beijing tend to vary markedly, featuring more or less prominently in EU member states’ domestic foreign policy debates.255 Poland, for instance, prioritises the EU and the US over China. Warsaw is happy to rely on the EU-China Strategic Partnership framework to guide its relations with Beijing. Countries like Spain and Bulgaria are attracted by the opportunities stemming from exports to a fast-recovering Chinese economy, all the while being wary of dependence on the Chinese market. Italy has been eager to catch up with Germany and France in attracting Chinese investment, though the efforts have not paid off and the country struggles to find a domestic political consensus. France is among those pushing for a pan-European approach to China, which takes into account, among other things, Beijing’s human rights violations as well as its role as a major development donor and economic behemoth.256 Ultimately, there is no consolidated consensus as to whether China is a strategic rival or partner (or both).257 The increased wariness and scepticism towards Beijing following the Covid-19 pandemic might just provide Brussels with momentum to establish a common EU strategic approach to China.

The picture is hardly more homogenous when it comes to EU member states’ views of the transatlantic relationship. Some capitals favour strong engagement with Washington beyond security (Dublin, Stockholm and Amsterdam among them), others would like to keep the focus of transatlantic relations on security, while others still are pushing for disengagement and greater European autonomy, Paris and Berlin included.258 Some member states value the US and Nato security umbrella more than others, which means that they also disagree on the extent to which American concerns should matter to the EU. Remarkably, while more than half of EU citizens think that the Union shares common economic interests with Washington, only 22% of EU citizens believe their country shares similar values with the US.259

In short, the polling suggests that the EU should pursue increased global leadership, but foreign policy is of little importance to most Europeans—especially among the younger generations. European citizens are keen to have a common foreign policy, but are wary of the associated constraints, like increased defence budgets and military interventions abroad. They are happy for the perks of global leadership to fall their way, but without the unpalatable responsibilities that come with it. Moreover, the different strategic outlooks and foreign policy traditions of 27 different member states, which encompass key issues such as EU−China and EU−US relations, stand in the way of a more effective EU in the world.

Despite broad support for a common European foreign policy that extends across cohorts and generations, much of that support erodes and national interest often prevails in the face of the costs and constraints of such a common foreign policy.

Finally, young Europeans prioritise environmental, educational and socioeconomic issues over foreign policy. Over the past decade the EU has nonetheless made some progress in advancing the Union’s global role.

What the EU is and is not doing

In his 2018 State of the Union address, Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker declared that “the hour of European sovereignty” had come: the EU was to live up to its global responsibilities and exercise its ability to shape the world (Weltpolitikfähigkeit) by becoming a more autonomous player.260 The current Commission’s six key priorities for 2019-2024 include building a stronger Europe in the world, initiating a new push for democracy and promoting the European way of life.261

As part of the first goal, current Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has expressed her commitment to lead a “geopolitical” Commission.262 Josep Borrell, the EU foreign policy chief, declared that the EU must learn to speak the “language of power” and to act alone to pursue its interests if necessary.263 In November of 2020, von der Leyen vowed to take “further bold steps in the next five years towards a genuine European Defence Union”, in order to continue the progress made by her predecessor.264

Beyond the rhetoric, both the Juncker and von der Leyen Commissions have started putting the EU’s money where its mouth is. The 2016 EU Global Strategy is an attempt at guiding current common EU foreign policy. EU member states thereafter agreed on the Strategy’s Implementation Plan, which established a number of decision- making tools and capability goals necessary for conducting a common foreign policy. As part of this effort to boost Europe’s influence in global affairs, the Commission launched the European Defence Fund (EDF) in 2017.265 The EDF helps members define their defence needs and coordinate throughout the industrial cycle—including research, development of prototypes, and eventually, the acquisition of defence capabilities. Ambitious cooperative defence projects are thus jointly funded by the EU and the individual member states. In 2017, 25 member states joined the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), which creates a framework for those member states that are willing and able to cooperate more closely in the field of security and defence.266 A complementary initiative to both the EDF and PESCO is the Coordinated Annual Review of Defence (CARD). The main aim of CARD is to provide a regular assessment of member states’ defence capabilities, identify any strategic capability gaps and suggest areas for potential cooperation at the EU level.267

In the wake of the 2016 EU Global Strategy, member states also agreed on the establishment of the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC), de facto creating “a small cell working as an EU defence command”.268 The MPCC oversees operational planning and conduct of non-executive military operations, such as the EU Training Missions in Somalia, Mali and the Central African Republic.269

Additionally, when von der Leyen took office in 2019, a new Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG Defis) was instituted to oversee the management and implementation of the EDF and the EU Space Programmes—such as the Galileo satellite navigation system and the Copernicus Earth observation system.270 A concrete step towards the creation of a geopolitical Commission, the new DG is indicative of a qualitative shift in the Commission’s role in the area of security and defence. More recently, the EU adopted the European Peace Facility, an off-budget fund worth approximately €5 billion for the period 2021-2027, to be financed through contributions from EU member states. Improving upon previous financial instruments, the European Peace Facility creates one single instrument to finance EU foreign policy operations and missions in the defence field.271

To ensure coherence among all these different tools, the Council has decided to draft a Strategic Compass, which is to be completed by 2022. The Compass should provide guidance for the consistent use of existing initiatives and define policy orientations, specific goals and objectives in areas such as crisis management, resilience and capability development.272

The EU has also made progress beyond the field of foreign and security policy proper. For instance, it is flexing its regulatory muscles by adopting standard- setting measures such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and is leveraging its trade power to assert its interest vis-à-vis China.273 The Comprehensive Agreement on Investment adopted in December 2020 shows as much. In principle, the trade deal should help balance the EU−China trade relations by allowing EU companies to compete on a level playing field against Chinese state-owned companies and reducing barriers to entry in certain sectors (e.g. eliminating joint-venture requirements), such as manufacturing, financial services and air transport.274 In turn, the EU is using the Agreement to put pressure on China with respect to both its sustainable development commitments - such as those contained in the 2015 Paris Agreement - and international labour standards. (However, there is now serious doubt as to whether it will finally come into force.)

While there are still differences (regarding the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, for instance), the EU27 have also been uncommonly disciplined and united in their positions on Russian sanctions, and most agree on the necessary conditions to lift them.275 After Russo-Ukrainian tensions rose again in the spring of 2021, European unity and solidarity was put to the test on this front.276

Despite the progress made towards strengthening the EU’s global influence, there are critical steps that the EU is not taking. The latest seven-year budget attests to Brussels’ commitment to combating climate change and investing in digital innovation. The budget allocated to Europe and its neighbourhood, however, was cut from the initial €118 billion proposed to €98 billion—despite featuring in the Commission’s stated priorities for 2019-2024.277 More broadly, despite the headway made over the last decade, genuine European strategic autonomy—including the decision-making tools required to act efficiently and expeditiously—is not in sight. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown the extent to which disagreement between EU member states, coupled with limited powers in the hands of the Commission, make for a dependent and slow European Union.

Nor did the Commission’s endeavours on vaccine export controls meet a better fate in Northern Ireland. They sparked outrage on both sides of the Irish border and forced Ursula von der Leyen into a humiliating about-face. They were reminiscent of the Commission’s Association Agreement with Ukraine insofar as they seemed to come from an economic perspective and, paradoxically for a geopolitical Commission, disregard the political and geopolitical consequences.

Finally, turf wars between the various EU institutions have long been rampant, and they sporadically cause harm to the EU’s international credibility. At an April 2021 EU−Turkey summit in Ankara, Commission President von der Leyen was blindsided, “when European Council president Charles Michel and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan sat in armchairs next to each other—leaving her to sit alone on a sofa”.278 Apart from the image of inherent sexism it projects, such display of internal divisions among EU institutional figures provide partners and rivals with a sense that the EU is weak and divided. Even when it is one single EU figure that should confront international crises, there too the Union is still struggling to assert itself. This lingering weakness could not have emerged more starkly than during High Representative Joseph Borrell’s unfortunate trip to Russia in February 2021.279 Lacking the necessary mandate from the EU27, Borrell was incapable of responding to Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov’s dismissal of the EU as an “unreliable partner”, exposing Brussels to ridicule and feeding into an old narrative about the EU’s diplomatic inexperience. High-stakes diplomacy still proves difficult for EU representatives who lack any actual leverage to force the hand of partners and rivals alike. On the whole, however, former Belgian Foreign Minister Mark Eyskens’ pronouncement that Europe is “an economic giant, a political dwarf and a military worm” does not ring as true today as it might have in the 1990s.

What we think the EU should do

The EU and its institutions have recently sought to position themselves as ‘geopolitical’ actors. Alas, while the narrative may help focus minds in theory, it has also come up against a string of disheartening setbacks in practice. In the short term, EUrope should either strive to fulfil its geopolitical ambitions in practice, or consider toning down its overarching rhetoric and underlying assumptions.

The past few years have also exposed some of EUrope’s underlying weaknesses. From the continent’s industrial dependency on China to its legal vulnerability to US secondary sanctions; from its over-reliance on Russian energy exports to its lack of muscle in technological innovation, there is a slew of paralysing capability gaps that hamper the credibility of the EU’s external action. In response, Europe should first acknowledge that, from Personal Protective Equipment to 5G and from drones to semiconductors, there is no aspect of everyday life in Europe that does not involve an external element.

In place of generic foreign policy ambitions, this should push Europe to identify the specific, tangible areas it wishes to shape in technological, ecological, industrial or military terms—and conversely locate more clearly those in which it is happy to choose its dependencies. From there, the EU should make sure it is in the position of having a hand in shaping these areas, as opposed to meekly charting the path that is leading Europeans into a world that changes on the whim of other powers. To adapt Radek Sikorski’s famous statement on German foreign policy, we fear European power less than we are starting to fear European inactivity. 280

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, a political consensus appears to have solidified around the notion of strategic autonomy, including in capitals that previously shunned the concept as French grand strategy. On the consistent and enduring evidence that Europeans call for a more influential Union and a common EU foreign policy, we think that the EU should seriously commit to the goal of strategic European autonomy in theory and practice. This means that the EU should have capacity for autonomous action and the decision-making tools to guarantee it. Strategic autonomy would allow the EU to be a better Nato ally, a more influential actor within multilateral institutions and a more autonomous player, free and able to pursue its interests when necessary. Joint procurement and greater interoperability across the EU27 armies would enable EU member states to build up the capabilities that the US has long been demanding.

Critically, strategic autonomy does not mean that the EU should—or, indeed, will— act alone, but simply that it should be prepared to do so to pursue its interests.281 A Europe that is better able to leverage its capabilities will be a better champion of multilateralism and a more effective partner for the United Nations as well as regional organisations, from the OSCE to the African Union. A more capable and autonomous EU would also be a more influential player in its own neighbourhood. With the US mainly preoccupied with domestic issues and its rivalry with China, the EU must also engage more effectively in its neighbourhood, starting from the Western Balkans, which are moving away from the acquis communautaire and closer to ‘stabilocracy’. Governance in the Western Balkans is drawing increasingly on “the Chinese and Russian models of authoritarian capitalism, based on predatory state behaviour, state capture and corruption”.282

Europe should go further and ask itself whether it has a strategic story that resonates both at home and across the world. Is it a Europe of peace? A prosperous Europe? A sponsor of effective multilateralism and global governance? A green superpower? An actor committed to protecting the global commons to protect the citizens of the EU? A combination of all the above? At the very least Europe should seek to clarify the notion of Europe as a ‘geopolitical’ actor. For the greater part of its history, the EU’s very specificity lay in the fact that it was the anti-geopolitical actor par excellence. It was built to overcome the worst effects of geopolitics on European soil, and to mitigate the more egregious consequences born of zero-sum approaches outside of Europe. In doing so, Europe should take more care to factor in the perceptions of the younger generations of Europeans, who—among other things—do not place as great an emphasis on hard borders.

Indeed, our polling and webinars suggest no solid consensus exists amongst Europeans, young and old, around the idea of Europe as a typical geopolitical superpower. Across generations, the data is skewed instead towards Europe as a green, civilian superpower. We therefore think the EU should remain a strong sponsor of multilateralism, rely on alliances and continue acting from within international organisations. But it should not shy away either from leveraging its economic, regulatory and trade power against strategic rivals and competitors—mindful though it should be of power asymmetries when engaging with less powerful negotiating partners. While Europe may have been comfortable advocating for multilateralism in an American-led global order, for example, should it remain so in the context of a Chinese-led multilateralism?

In short, Europe should craft a distinctive strategic story for the 21st century. Beyond the EU’s work on the “Strategic Compass” and some deeply rooted differences in threat perception, Europe should work on a positive European understanding of where common interests lie. To achieve this, the continent must chart a course between bottom-up strategic cacophony and top-down euphony by folding the rich patchwork of national perceptions into a strategic polyphony of common interests. 283

As a civilian superpower, Europe needs a story that allows it to uphold its common interests, but within the limits of its own model and the constraints of its own history. A model that does away with the imperial past of geopolitics, but which nonetheless allows the EU to defend its common interests and shared values in a world of private and public superpowers. A language that goes beyond elite foreign policy ‘narratives’ and allows it to lead the way in charting a course that is more inclusive and less extractive—but nevertheless empowers the EU to persistently defend its choices when they are threatened. A toolbox that can achieve a strong common external policy— but does not overlook the fact that Europe lives in a world that is no longer Eurocentric. It remains for Europe to weave these different dimensions into coherent and convincing political discourse.

Overall, there is little Europeans can do without a global Europe. Recognising that nothing that concerns people’s everyday life in Europe is devoid of an external dimension can contribute to a strategic story, as opposed to an elite foreign policy narrative that better resonates with European citizens. As a green civilian superpower, Europe might seek to reunite and reconcile the protection of the environment, the protection of its citizens and the protection of the European project. It should argue that all three dimensions are mutually reinforcing. In short, and to capture it in metaphorical terms, Europe’s strategic story should aim to fashion a middle ground between the image of the original princess Europa, passively kidnapped in Titian’s painting, and the Europa Regina of Sebastian Münster’s sixteenth century prints, in which Queen Europe is represented, orb and sceptre in hand, as the aggressive promoter of the faith.

Lastly, Europe should be in a position to rally around the red lines that come from its shared values and fold them into this distinctive strategic story. As suggested in Chapter 5, it should focus on the values that it can credibly defend—in particular, those legally enshrined in the treaties. Defining such red lines will only be helpful, however, if the EU is prepared to stick to them, and knows where and when to defend them. If the EU is serious about defending its own red lines in a pluralist world that has provincialised Europe, then it should act accordingly vis-à-vis China and Russia, but also where necessary with the United States—all regional powers with their own red lines. Initiatives such as the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment might be a first step towards leveraging the Single Market not just against weaker trade partners,284 but against superpowers that consistently disregard human rights. Similarly, the proposal for an EU Border Carbon Adjustment Mechanism, a tool not too dissimilar from a CO2 tariff on imported products, would help put pressure on third countries to curb their greenhouse gas emissions.285 Europe’s red lines should include the fight for democratic values and human rights as well as a strong commitment to battling climate change.

Europe as a green civilian superpower has the potential to accommodate both its interests and values, by setting and protecting its red lines of its own, as and when they are threatened. Young Europeans place great emphasis on certain common values particularly the promotion of democracy, the freedom to travel, the protection of LGBTQ+ rights, the fight against climate change and a dislike of both internal and external borders. Visibly standing up for such values would contribute to making sure Europe’s story resonates in practice with coming generations—both the millennials of “Generation Z” and the “Generation C” of baby-zoomers shaped by the coronavirus pandemic. The range of these issues will be further explored in the next phase of the Europe’s Stories project, which will focus on ‘Europe in a changing world’.

To conclude, we would highlight four of our suggestions as follows. The EU should curb its damaging institutional infighting and be more prepared to look at issues from the outside in—rather than from Brussels out..

The European Union must steer clear of the inflated rhetoric that risks discrediting the Union’s reputation on the world stage, when it is not matched by concrete results. The EU should strive instead to under-promise and over-deliver in its international commitments.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, Europe’s political consensus has rallied around the notion of strategic autonomy. EU member states and institutions should push ahead and act on this consensus. As Europe transitions from the role of reactive strategic spectator to that of proactive global actor, it should endow itself in practice with the requisite degree of strategic, technological and industrial autonomy.

Finally, Europe should craft a distinctive strategic story which insists on its role as a green civilian superpower fit for 21st century purpose. It is a story that would help uphold common values, defend shared interests, and also allow Europe to nurture a global outlook. In turn, it would fortify the Old Continent's specific voice on the world stage as a strategic actor with a singular past but an uplifting future. This story draws on a polyphony of EUropean voices, cultures and generations. It is intuitively in tune with the preoccupations of young Europeans, and therefore more intuitively in tune with Europe’s future.

246 Directorate-General for Communication, "Standard Eurobarometer 92: Europeans' opinions about the European Union's priorities", European Commission, Autumn 2019, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/33119d82-f3d4-11ea-991b-01aa75ed71a1/. ↩

247 Ibid., 102. ↩

248 Catherine E. de Vries and Isabell Hoffmann, "A Source of Stability?", eupinions, 6 Sep 2017, https://eupinions.eu/de/text/a-source-of-stability. ↩

249 Europe's Stories, "Interview with David Gill", europeanmoments.com, 2021, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/david-gill. ↩

250 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Sylvie Kauffmann", europeanmoments.com, 2021, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/sylvie-kauffmann. ↩

251 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Robert Grzeszczak", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/robert. ↩

252 Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, Directorate-General for Communication, "Flash Eurobarometer 478: How do we build a stronger, more united Europe? The views of young people", European Commission, Apr 2019, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2224_478_eng?locale=en. ↩

253 Directorate-General for Communication, "Special Eurobarometer 486: Europeans in 2019". ↩

254 Garton Ash et al., 26 Jan 2021. ↩

255 Ulrike Franke and Tara Varma, "Independence play: Europe's pursuit of strategic autonomy", ECFR Flash Scorecard, 18 Jul 2019, https://ecfr.eu/special/independence_play_europes_pursuit_of_strategic_autonomy/ ↩

256 Janka Oertel, "The new China consensus: How Europe is growing wary of Beijing", ECFR Policy Brief, 7 Sep 2020, https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_new_china_consensus_how_europe_is_growing_wary_of_beijing/. ↩

257 Claire Busse, Ulrike Franke, Rafael Loss, Jana Puglierin, Marlene Riedel and Pawel Zerka, "Policy Intentions Mapping" ECFR Special, 8 Jul 2020, https://ecfr.eu/special/eucoalitionexplorer/policy_intentions_mapping/. ↩

258 Ibid. ↩

259 Catherine de Vries and Isabell Hoffmann, "Together apart", eupinions, 28 Oct 2020, https://eupinions.eu/de/text/together-apart. ↩

260 Jean-Claude Juncker, "President Jean-Claude Juncker's State of the Union Address 2018", European Commission, 12 Sep 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_18_5808. ↩

261 European Commission, "The European Commission's priorities", European Commission, 16 Jul 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024_en. ↩

262 Ursula von der Leyen, "Speech by President-elect von der Leyen in the European Parliament Plenary on the occasion of the presentation of her College of Commissioners and their programme", European Commission, 27 Nov 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_19_6408. ↩

263 Josep Borrell, "Hearing with High Representative/Vice President-designate Josep Borrell", European Parliament, 7 Oct 2019, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20190926IPR62260/hearing-with-high-representative-vice-president-designate-josep-borrell. ↩

264 Ursula von der Leyen, "State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary", European Commission, 16 Sep 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_1655. ↩

265 European Commission, "Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs", European Commission, Jun 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/defence/european-defence-fund_en. ↩

266 Alessandro Marrone, "Permanent Structured Cooperation: An Institutional Pathway for European Defence", IAI , Nov 2017, https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/permanent-structured-cooperation-institutional-pathway-european-defence. ↩

267 Ibid. ↩

268 Jean-Pierre Darnis, "The Future of EU Defence: A European Space, Data and Cyber Agency?" IAI Commentaries, Oct 2017, https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/permanent-structured-cooperation-institutional-pathway-european-defence. ↩

269 Council of the EU, "EU defence cooperation: Council establishes a Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC)", Council of the EU press release, 8 Jun 2017, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/06/08/military-mpcc-planning-conduct-capability/. ↩

270 Directorate-General Defense Industry and Space, "Strategic Plan 2020-2024", European Commission, Sep 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/info/system/files/defis_sp_2020_2024_en.pdf. ↩

271 European External Action Service, "Questions & Answers: The European Peace Facility", European Commission, 22 Mar 2021, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/46286/questions-answers-european-peace-facility_en. ↩

272 Council of the European Union, "Council Conclusions on Security and Defence", Council of the European Union, 17 Jun 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/44521/st08910-en20.pdf. ↩

273 Thomas Raines, "Raise the Bar by Leveraging the EU's Regulatory Power", Chatham House, 12 Jun 2019, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2019/06/raise-bar-leveraging-eus-regulatory-power. ↩

274 Philippe Le Corre, "Europe's Tightrope Diplomacy on China", Carnegie, 24 Mar 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/03/24/europe-s-tightrope-diplomacy-on-china-pub-84159. ↩

275 Kadri Liik, "Winning the normative war with Russia: An EU-Russia Power Audit", ECFR Policy Brief, 21 May 2019, https://ecfr.eu/publication/winning_the_normative_war_with_russia_an_eu_russia_power_audit/. ↩

276 BBC, "Russian 'troop build-up' near Ukraine alarms Nato", BBC News, 2 Apr 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56616778. ↩

277 Nathalie Tocci, "European Strategic Autonomy: What It Is, Why We Need It, How to Achieve It", Instituto Affari Internazionali, 26 Feb 2021, https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/european-strategic-autonomy-what-it-why-we-need-it-how-achieve-it. ↩

278 Ayla Jean Yackley and Michael Peel, "EU-Turkey in blame game over 'sofagate' after Ursula von der Leyen left standing", Financial Times, 8 Apr 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/95451ed1-a676-4b4a-ab71-8282fdc96d6e. ↩

279 Matthew Karnitschnig, "EU foreign policy RIP", Politico, 13 Feb 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-foreign-policy-rip/. ↩

280 Radosław Sikorski, "Speech to the Allianz Forum", DGAP, 28 Nov 2011, https://dgap.org/en/events/i-fear-german-power-less-german-inaction. ↩

281 As Nathalie Tocci has pointed out, autonomy "does not necessarily entail is independence, and still less unilateralism or autarky" (in Tocci, "European Strategic Autonomy"). ↩

282 Ibid. ↩

283 For a discussion of the concept, see Olivier de France and Nick Witney, "Europe's Strategic Cacophony", ECFR Policy Brief, 25 Apr 2013, https://ecfr.eu/publication/europes_strategic_cacophony205/; and Hugo Meijer and Marco Wyss, "L'impossible renaissance de la défense européenne: généalogie d'une cacophonie strategique", Le Grand Continent, 2019, https://www.sciencespo.fr/ceri/fr/content/l-impossible-renaissance-de-la-defense-europeenne-genealogie-d-une-cacophonie-strategique-0. ↩

284 The EU's tendency to follow a carrot-and-stick approach vis-à-vis many developing countries has been highlighted, among others, by Sophie Meunier and Kalypso Nicolaïdis, "The European Union as a conflicted trade power", Journal of European Public Policy, 13 no. 6, (2006): 906-925, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13501760600838623. ↩

285 Jan Cernicky, "Trade and Environment: The Prospects of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism", ISPI, 18 Mar 2021, https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/trade-and-environment-prospects-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-29579#n1. ↩