What young Europeans want EUrope to do

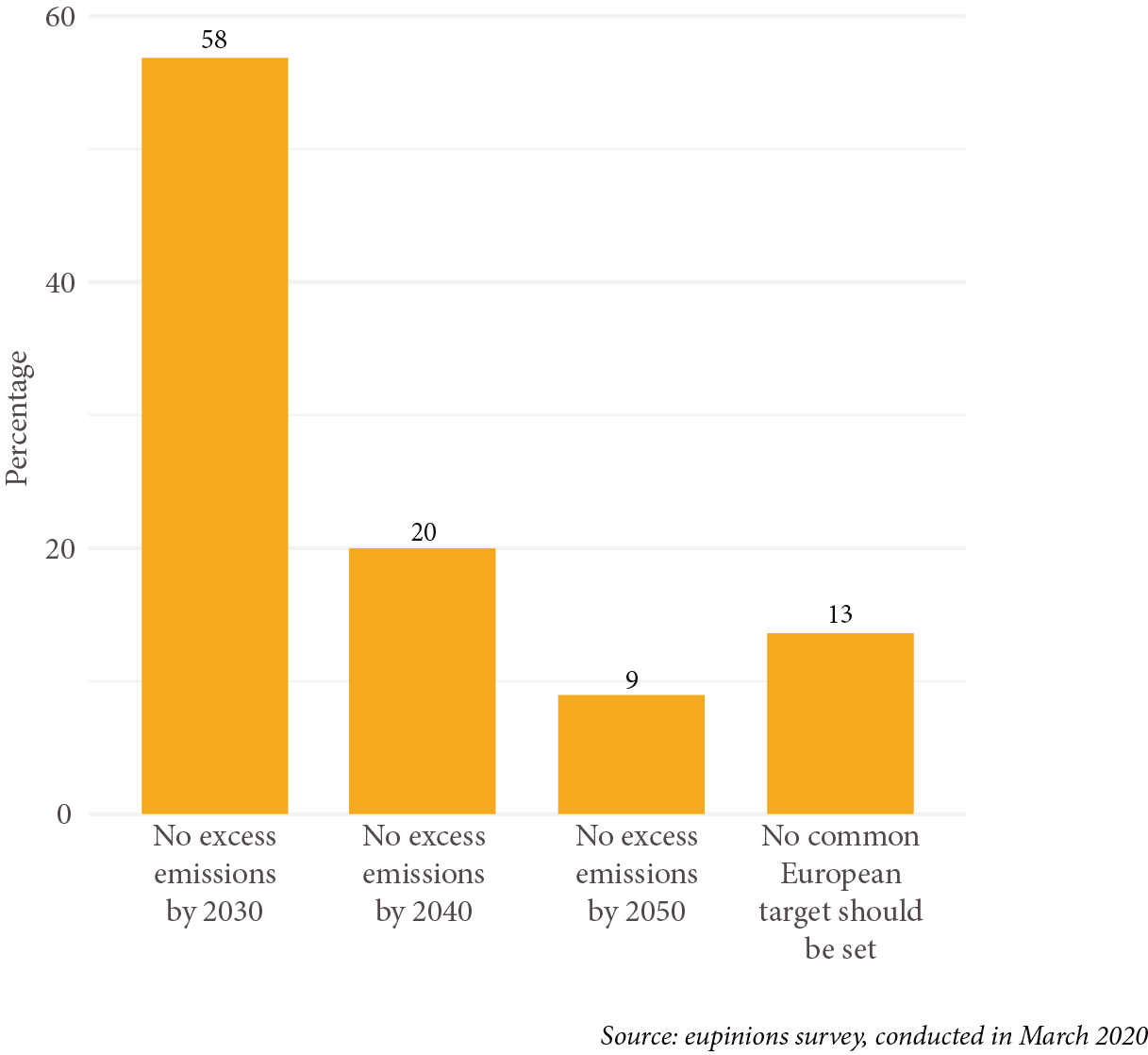

Our polling on climate change has found Europeans across age groups are largely united in what they want the EU to do. Most Europeans (58%) in our March 2020 polling want the EU to be carbon neutral by 2030, with an additional 20% aiming for 2040.87 Europeans across all age groups see a range of different political actors as responsible for achieving this goal, including national governments. In particular, young Europeans place more emphasis on international institutions and local governments than older generations. Our qualitative research suggests that this focus on a wide range of institutions emerges from young Europeans’ sense of urgency about the matter. For example, a policy expert from Hungary born in 1991 says:

“Deal with climate change or energy efficiency programmes. It’s a very challenging area we have to find the right answers, the right common answers at a European level. It’s not a national level problem, it’s a global level problem, so we have to be united, unite in [...] an action plan or something like that.” 88

The belief that individuals bear the primary responsibility for climate action is almost constant across age groups (33%). Young people are not more likely to think that individuals bear the primary responsibility, and do not emphasise consumerist habits more than other age groups.89 This is one of the criticisms often made of the youth climate movement, especially in high-income countries. It is argued that members of Generation Z or “Generation Greta” want everyone and everything to change drastically, but they are not willing to give up their own living standards.90 However, studies of the Fridays For Future movement have shown that its activists are indeed willing to give up certain individual privileges,91 and are ready for “slower economic growth and some loss of jobs” as a result of more climate action.92

Figure 9

Carbon emissions stemming from cars, planes and industries are an important driver of climate change. How quickly should EU countries reduce their carbon emissions in a joint effort?

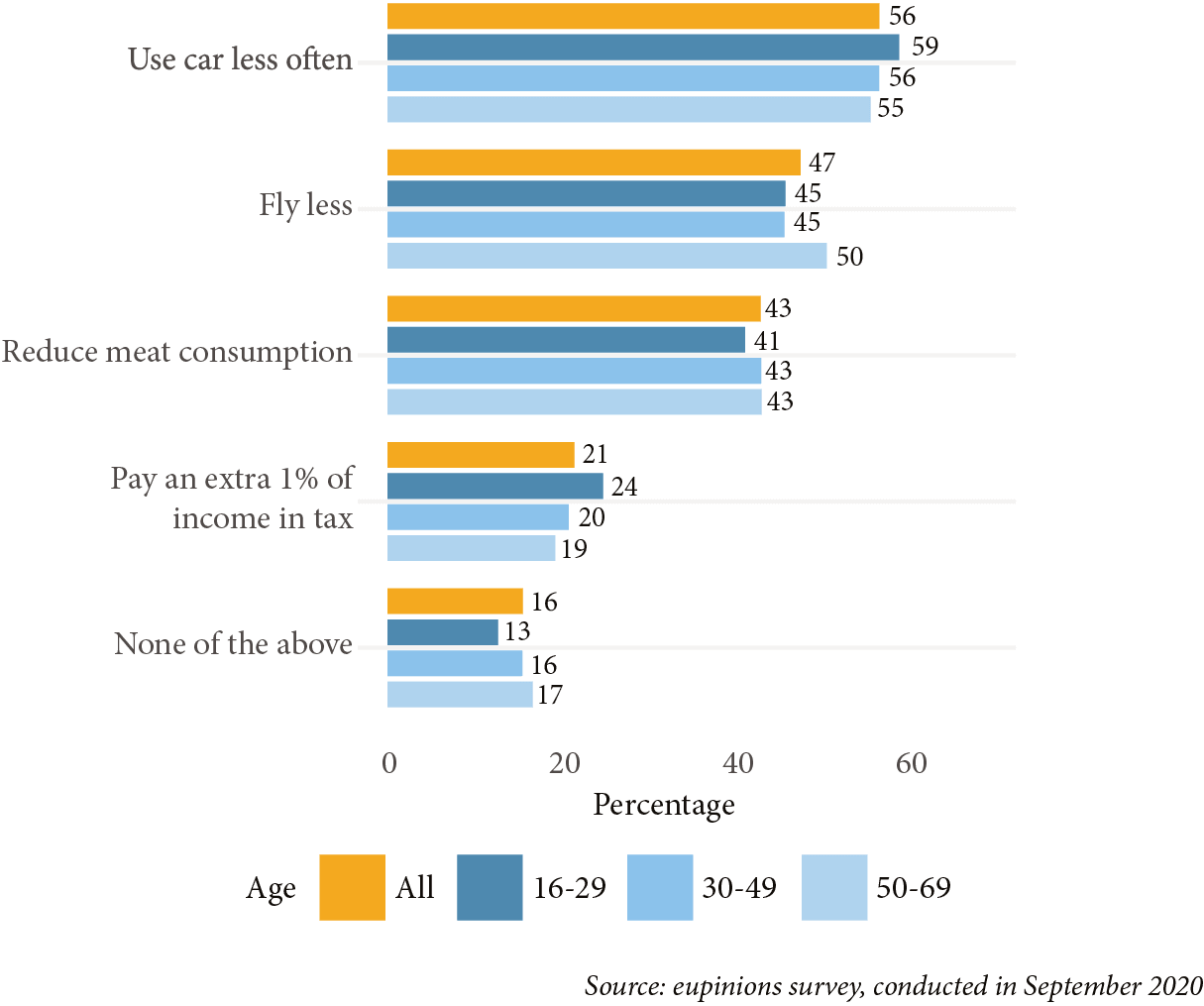

Overall, the Fridays For Future movement recognises the importance of individual actions but aims to steer away from solely blaming individual consumers. Instead, they emphasise the responsibility of politicians, arguing they need to recognise climate change as a matter of utmost urgency.93 Fittingly, young Europeans are more likely to suggest that governments impose a carbon tax to transition away from fossil fuels, and to suggest that governments focus on establishing re-training programmes for fossil fuel employees. In contrast, older age groups are more likely to emphasise subsidising renewable energy. Similarly, and most strikingly, young Europeans seem more willing to accept restrictions in order to combat climate change than older generations. For example, our September 2020 poll revealed that almost two-thirds of young Europeans are willing to accept the restriction of dietary choices to vegetarian and vegan in public eating facilities.94 Yet in the same poll, we found that young Europeans are slightly less likely than other age groups to think the EU is not doing enough to combat climate change—even though a staggering 69% believe the EU is not doing enough.95

This finding is corroborated in the Eurobarometer 501.96 We cannot infer from our data, but it is possible that this willingness to accept more restrictions and to demand more ambitious climate targets while being slightly less critical of the EU, is the result of young Europeans regarding a wider array of actors as responsible. This is supported by the Eurobarometer 490, which shows that Europeans aged 15–24 are more likely to see all actors offered to them in the survey as responsible for tackling climate change. Or, as a Finnish PhD researcher born in 1981, shared in her interview with us:97

“I think that the biggest burning problem of our generation or our time is for sure climate change. I see EU has a lot of potential...it’s such a big problem that one nation can’t really fight against that in an efficient way. So I think that’s really a field or a topic where EU has a lot to offer. But m> that EU is doing enough. So I would like to see EU really committing to a carbon-free society by 2030.”

In a similar manner, the Flash Eurobarometer 478, conducted in March 2019, finds that the vast majority of young Europeans believe climate change should be a priority in the EU for the years to come (67%). Moreover, 41% of them believe that climate change, the environment, and eco-friendly behaviour are not given sufficient coverage in the school curriculum.98

In agreement with our own polling, an extensive cross-European study focusing on the individual-level determinants of climate change perception by Poortinga et al. shows that the age effect varies across countries. In almost all studied countries, older respondents were more likely to question the attribution of climate change to humans.99 However, in 10 out of the 23 studied countries, the association was insignificant between age and the following factors: climate perception (as a risk or concern); seeing a trend towards global warming; seeing negative impacts; general concern about climate change. This shows a great variability of the age-effect depending on context and type of concern about climate change.

Of course, this does not mean there is no age gap at all. It mainly points to the fact that the relationship between age and attitudes towards climate change, as well as expectation from the EU, is less straightforward than the emergence of the Fridays For Future movement or previous scholarship from the US might suggest.100 Our research finds that there might be a stronger period effect, as Europeans across all age groups are currently concerned about climate change. Taking a more nuanced view on climate change attitude demonstrated by Poortinga et al., we thus argue for a minor age effect.

It is mainly the concern for climate change which is similar across age groups. There is a more significant divide regarding the kind of actions that should be taken to tackle global warming. In line with demands made by current youth movements, our polling shows that young Europeans are more in favour of strong climate change interventions, such as restricting diets in public spaces, restricting car use or increasing taxes. However, together with the middle-range age group, they are less likely than older Europeans to support a ban on short-haul flights and the most likely to support national governments bailing out national airlines following the Covid-19 pandemic. This emphasises that while young Europeans seem to believe restrictions to individual behaviour are important, that does not make them more likely than other age groups to support interventions in areas they are most affected by.

Figure 10

Which of the following actions, if any, would you be ready to take to help combat climate change? (Select all that apply.)

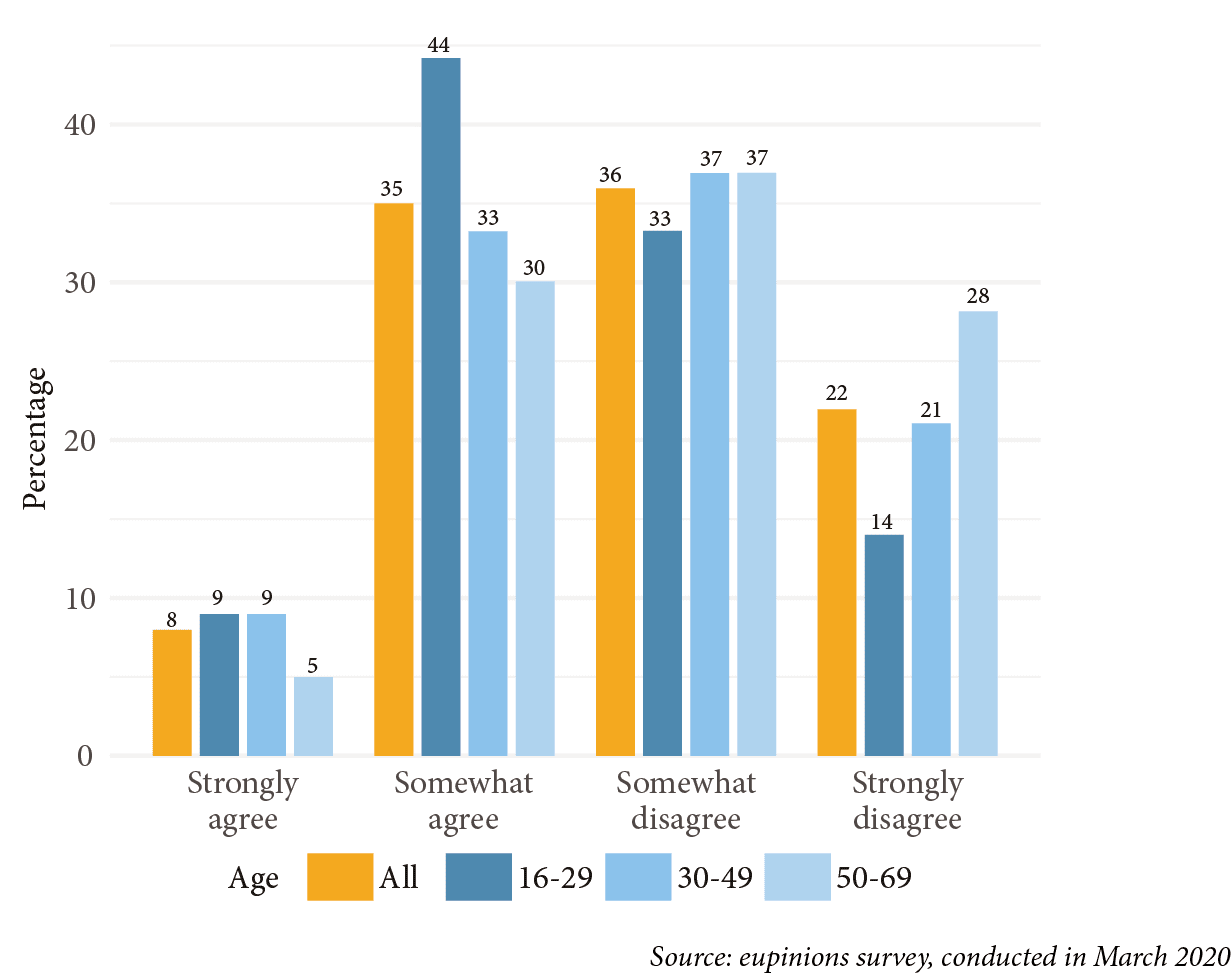

Furthermore, our March 2020 polling suggests that 53% of young Europeans believe that authoritarian states are better equipped than democracies to tackle the climate crisis.101 This does not mean that young Europeans do not value democracy, quite the contrary (see Chapter 5, on democracy). Instead, it points to a strong sense of urgency and young Europeans wanting a multi-actor response to climate change, which includes increasing political pressure on either themselves, fellow citizens or perhaps businesses.

A similar conclusion is suggested by de Moor et al., who find that around three out of four respondents at global Fridays For Future protests agreed with the statement that “the government must act on what climate scientists say, even if the majority of people are opposed.” They argue that this is rather a sign of desperation than anti-democratic sentiment, as their respondents also preferred democracy over other forms of governments.102

Figure 11

Would you agree or disagree? "Authoritarian states are better equipped than democracies to tackle the climate crisis."

What the EU is and is not doing

Whereas a large majority of Europeans in our survey wanted the EU to aim for net zero emissions by 2030 or 2040, the EU is aiming for 2050, with a reduction of the net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030.103 In December 2019 the EU announced the European Green Deal—a plan to move towards a sustainable economy, restore biodiversity and cut pollution. The plan spans different policy sectors of the EU and entails initiatives such as the ‘New European Bauhaus’, an initiative for sustainable and innovative urban planning, or the European Climate Pact, which encourages citizens to become ambassadors for climate change and make connections between different European climate change actors, be it activists, institutions or individuals. As part of the European Green Deal, the EU also has long-term plans for structural change. This includes a roadmap to reach the climate target, or the European Climate Law, which turns “this political commitment into a legal obligation”,104 and of course the Just Transition Fund, which provides financial support for those most affected by the move towards a sustainable economy.

In addition, 37% of the post-pandemic recovery funds have been reserved for the green transition—amounting to a sum of €265 billion.105 This programme forms part of the European Green Deal’s Investment Plan to further connect finance with sustainability by mobilising and stimulating sustainable public and private investment.106 In the context of the Investment Plan, the European Commission has, for example, declared the plan to develop a EU Green Bond Standard. This voluntary EU-wide standard is necessary for establishing what is considered ‘green’, defining the best practice in reporting and verifying sustainability indicators and for improving the comparability across the market.107 Eventually, this aims to increase the effectiveness, transparency, credibility and comparability of the green bond market, which is of growing importance for encouraging real economic investments in green assets and infrastructure. In order to qualify for Investment Plan funds, a project must contribute to one of the EU’s six environmental objectives and “do no significant harm” to the other five objectives: climate change mitigation; climate change adaptation; sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources; transition to a circular economy; pollution prevention and control, protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.108

However, there are several voices raising concerns about the distribution of these funds. Firstly, national governments will be in charge of the distribution of the funds. Whereas the EU demands that member states apply to the fund with a spending plan and reserves the right to scrutinise the plans, the reactions on whether or not the green regulations go far enough have been mixed.109 Many have raised concerns about loopholes that will increase mismanagement of funds and decrease the impact they will have on reaching the EU’s climate change goals.110 And in an interview we conducted, the mayor of Warsaw (and runner-up in the Polish presidential elections), Rafał Trzaskowski, points out how wanting to tackle climate change but not getting the necessary funds for it is one of the reasons why Warsaw, along with other major Eastern European capitals, has appealed to the EU for direct funding.

“We need help from the European Union, not only to the country, but also to the cities and regions and we are fighting for direct access to EU money. I’m afraid the EU government will use political criteria to redistribute money from the EU funds, and then it would be very difficult for us in the city to confront climate change.” 111

Secondly, the lack of a common EU fiscal policy gets pointed out, with Robert Habeck, co-leader of the German Green Party and MP, arguing in our interview with him that a common fiscal policy is needed to increase investments in renewable energies and to turn the green transition into a “success story”, that is, a transition Europeans are not afraid of any more.

Thirdly, as Wolfgang Münchau pointed out in one of the webinars we organised on the subject, there exist only three categories for ‘green investments’ in the EU: 0%, 40% and 100%. These three tiers are based on the ‘Rio markers’ which were originally developed by the OECD to quantifiably monitor development assistance.112 Each new EU project or policy is evaluated and assigned a weight as to whether it makes a ‘principal’ contribution to climate mitigation targets (100%), a ‘significant’ one (40%), or makes no contribution at all (0%).113 These categories, however, are aspirational, as numbers associated with each project are rounded up and projects are classified as a whole (even if only a part of the project makes climate action contributions), meaning everything which falls even slightly above 0% quickly falls into the 40% category and so on, aiding countries in greenwashing their recovery plans.114 Furthermore, plans with low (or no) ‘contribution’ to climate mitigation are not immediately downgraded in priority and must only show that they ‘do no significant harm’ to the climate.115

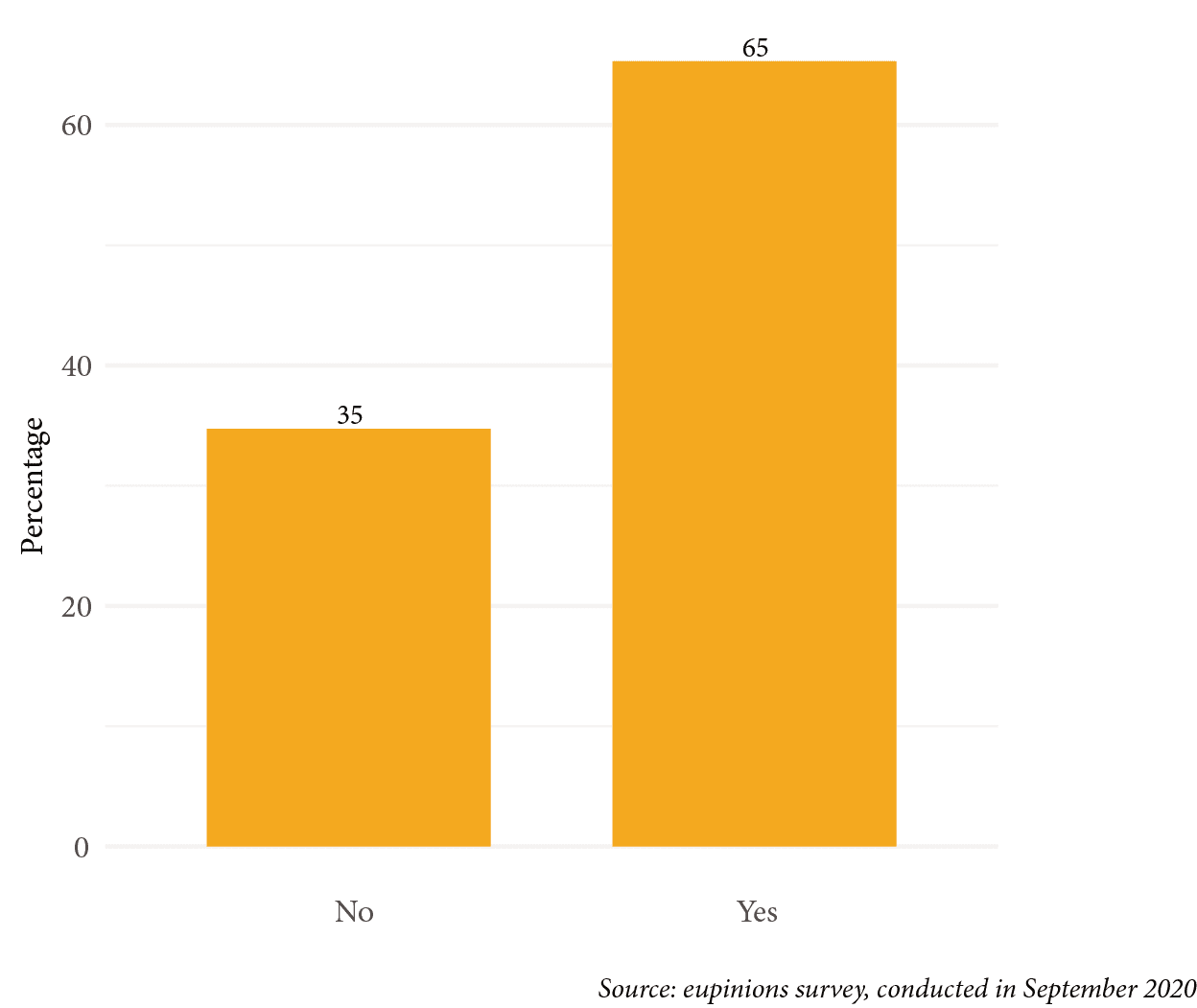

Figure 12

To help combat climate change, would you support a ban on short flights to destinations that could be reached within 12 hours by train?

Finally, there is also a more radical critique of the EU, which argues that the EU is generally ‘a bad thing’ for climate. For example, George Monbiot, a political activist and journalist known for his climate activism, argues that national governments are able to hide behind the EU institutions and push through corporate interests they wouldn’t be able to get away with in their own national contexts.116 As an example, he points out the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), through which agricultural landowners receive funds, whether or not they need them, and are even incentivised to ‘set aside’ farmland. This threatens European wildlife, as farmers and investors recognise the financial potential in turning wildlife areas into unused farmland. In our webinar, Dieter Helm, a leading expert on the political economy of climate change, strongly agreed with this critique of the CAP.117

Considering what Europeans are willing to do to contribute to effective climate action in comparison to what the EU is currently doing, we find several discrepancies. Summing up our earlier findings, Europeans are largely united in thinking the EU does not do enough to combat climate change, and in wanting EU countries to reach net zero by 2030 or 2040. They see different actors responsible for it (from individuals to businesses, to different levels of political actors) and see investment in renewable energies as the best course of action to move away from fossil fuels. On a more individual level, they are willing to drive and fly less, but tend to prefer banning the form of transport their age group is less likely to engage in. However, our polling shows that two in three Europeans would support banning short-haul flights that could be replaced by train rides of up to 12 hours, which is a suggestion taken from the climate plan of the Swiss Young Green Party.118 Taken together, this data points towards Europeans wanting to move forward farther and faster with climate action, especially in areas where the impact on climate change is unmistakable.

What we think the EU should do

In its actions against climate change, the EU is still focusing on what it knows best: regulating, funding and setting goals. The recovery fund and the reserved 37% for a green recovery represent an important change in European fiscal policy. Moreover, the significance of the new climate law is not to be understated—although several major elements of the EU climate law proposed by the more ambitious European Parliament were watered down following long and intense debates with the Council and the Commission. For example, whereas the European Parliament called for an intermediary reduction target of 60% by 2030, in order to reach the 2050 goal, the European Council set it at 55%.119 Additionally, the carbon budget, which sets the amount of emissions the EU can emit in any given year while still staying on track to achieve their climate goals, as well as a rule that member states have to end fossil fuel subsidies, was only implemented minimally or not at all.120 We think that the Council and Commission should follow an intermediary reduction target of at least 60% and fuel subsidies. These suggestions are outlined by the European Parliament which is elected by the European public. In general, the Parliament’s proposals are closer to what Europeans want and therefore the Commission should follow the Parliament on climate policies in the future.

It is important to point out that not supporting the carbon budget element is related to the Commission favouring a net zero goal which allows for carbon offsetting, whereas the European Parliament calls for a reduction of real emissions. While some carbon offsetting can prove useful, climate change researchers have pointed out that there are not enough so-called ‘carbon sinks’ in the world to balance out worldwide emissions. Net zero is based on a logic which stems from accounting—the term does not capture the intricate mechanisms behind carbon offsetting, such as the risk of putting too much (emission) burden on nature (such as forests) or the difficulties of offsetting ongoing fossil fuels emissions in a short enough timespan.121 Consequently, the European Green Deal and the new European climate law might sound more promising and ground-breaking than they will be in reality. Shining a light on the still ongoing debates and subjecting them to scientific analysis makes any sense of optimism dwindle. Europeans want the EU to deliver, but the EU is the slow-moving institution it has always been. This does not mean that there is no room for improvement.

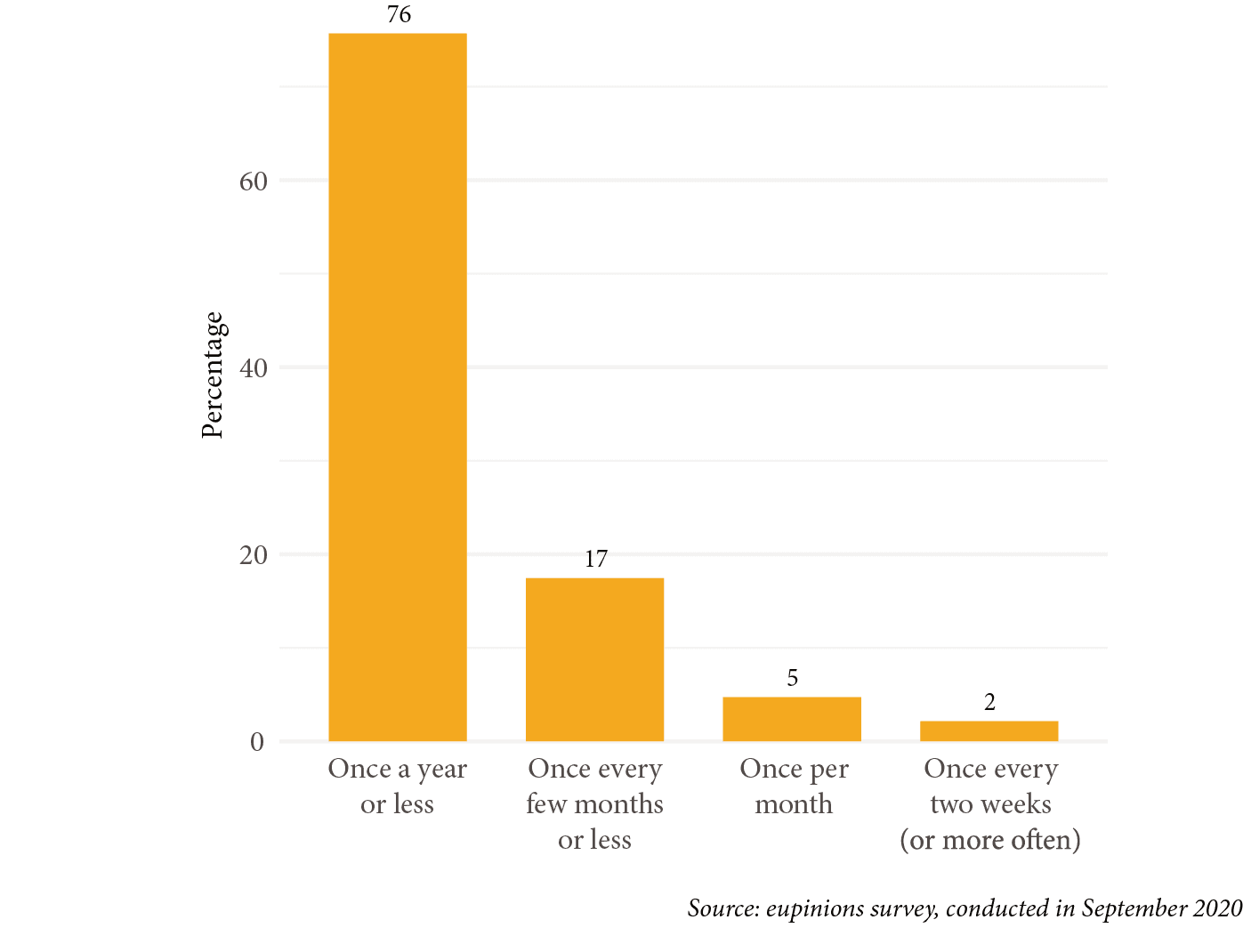

Figure 13

Prior to the outbreak of Covid-19, on average how frequently did you fly within Europe?

However, the European Parliament is not the non-plus-ultra of climate change policies either. Whereas its plans are generally more ambitious, it failed for example to address the issue of the CAP in an adequate manner and even cut down on some of the Commission’s climate targets in the CAP reform proposal. For example, the Parliament voted against an emission target of 30% for the agricultural sector by 2027 and refused to protect grasslands and peatlands.122 Yes, it demands a higher eco- scheme than the Commission (30% instead of 20%) which means that 30% of the direct payments budget is designated to flow towards ecological agriculture schemes,123 but this is not an excuse for failing to protect peatlands which store a significant amount of CO2, which is released if the lands are drained.124 On top of that, the Commission and the Parliament are struggling to come to a common definition of what an ‘active farmer’ is—clearing the way for further misuse of CAP funds by agricultural landowners. If the goal is net zero by 2040 or 2050, the EU has to be much more radical in reforming the CAP to address its negative contribution to climate change and must move beyond the impasse which has been created by the different vested interests in the EU.

This is not the only thing the EU can do to move closer to the expectations of Europeans. The EU has to become more specific and output-oriented. Keeping the EU’s climate action within traditional confines is not what is needed for a matter as urgent as climate change—and it is certainly not what young Europeans want the EU to do. The EU cannot solve climate warming for all of Europe, let alone the world though the new Biden presidency is leading to a renewed emphasis and interest in global climate action. But the EU can demonstrate what a climate policy for Europeans looks like and nudge its member states by leading by concrete example.

We want the EU to take proactive action towards cutting down short-haul flights. It should go beyond what France has done recently—outlawing short-haul flights which can be replaced by train rides of up to 2.5 hours—to ban flights which could be replaced by a train journey of under 12 hours.125 But what might banning short-haul flights in Europe mean? First, it would mean banning an activity which is harmful to the environment, but could easily be replaced by alternatives. Single- person car use is also very harmful (an argument which is often used against restricting air travel), but more difficult to replace or restrict without increasing already existing inequalities.126 Secondly, it would mean cutting a majority of all intra- European flights. If we take the EU definition of short-haul flights, meaning all flights of up to a 1500 km flight distance, and use a Central European city as the starting point, then most EU cities are within the radius. This remains true with the more conservative measurement using 12 hours of train travel time. For example, a London−Amsterdam business trip would still very much be feasible, as it takes roughly four hours by Eurostar. So would a holiday connecting Paris and Rome—a distance which can be covered in ten hours. Implementing restrictions based on travel time by train has the potential to be a more equitable approach to banning short-haul flights than banning by distance. It also carries the potential to start with a lower benchmark and expand the ban as train connections are improved. On top of that, flying is one of the most if not the most unequal and most carbon-intensive forms of consumption.127 Together with our short-haul flight question we asked Europeans how often they used to fly before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Our results re-emphasised what other research has also pointed out: a large majority of Europeans (76%) fly once a year or less. Combining this polling result with what we outline in previous chapters, we suggest the EU lead by example and ban its officials from taking short-haul flights for business trips if there is a train connection same route. For example, it is not very ‘next generation EU’ of the President of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, to travel from Riga to Berlin and on to Rome, all in one day, to officially hand over the NextGenerationEU recovery fund (to mention just one leg of her ‘tour des capitales’).

The EU should allocate more direct funding to regions or cities with ambitious climate targets. Building on our polling and our extensive set of interviews, we also suggest that the EU focus more on initiatives which deliver results that are clearly attributable to the EU. This does not mean changing the complete system, such as turning the EU into an even stronger supranational institution. Instead, it is about the EU showing determination, and signalling capability to handle climate change. Therefore the EU should allocate more direct funding to regions or cities with ambitious climate targets. This could even be framed as a competition between cities or regions, similar to that for the European Capital of Culture, which would help create a transition Europeans are “not afraid of anymore” (in the words of Robert Habeck). Alternatively, a climate change version of the “roaming success story” would also be an option,128 especially since reliance on funding schemes carries the risk of other actors (such as national governments) claiming the resulting projects for themselves, as funding sources can easily be left out or downplayed in relevance. To be clear, doing these things will not solve the underlying issue of weak emission targets. But as a supranational organisation with limited powers and finances, compared to all the member states taken together, the EU’s options are limited.

The EU should aim to improve the European railway system. In the short term, the EU should enable an easy-to-access online booking system for train journeys across the European continent. In the longer term, the EU should support a large-scale expansion of the European railway system and subsidise train fares. As a condition, the EU could require of national railway companies that all new and revived train connections carry a common European name. Through the interconnected nature of the railway system and the current lack of international cooperation in the railway system—exemplified by how difficult it is to book cross-national train rides compared to international flights—such a project would immediately become a recognisable European project.

In the past, the EU’s most ambitious targets became watered down in intra- institutional debates. For the future, the EU must thus make sure to take more action, as Europeans expect the EU to deliver, and young Europeans specifically want the EU to limit their options for (individual and collective) carbon-intensive behaviour. It is unclear if the EU has the legal and symbolic power to do what young Europeans expect them to do. From the EU’s perspective, this is a conundrum. But even just looking at our polls, it becomes clear that nobody expects the EU to solve it all at once. For example, this report did not focus much on the role of big businesses, as our work has mainly revolved around the European public, but their role is not to be understated either. However, being occupied with ambitious or less ambitious targets and regulations for itself and its member states can never be an excuse for not delivering on core areas such as agriculture or travel and failing to produce EU-specific output. Delivering is especially important in the case of climate change due to the increasing urgency of the matter, as well as the fact that it has been identified as a strategic priority of the new Commission. Thus, as we argued in an opinion piece published in the Guardian, one might even say that “to save Europe, they [European leaders] will have to save the planet.” 129

87 Garton Ash and Zimmermann, 6 May 2020.

88 Europe's Stories, "Interview with János Kele", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/janos. ↩

89 Renee Cho, "How Buying Stuff Drives Climate Change", State of the Planet, 16 Dec 2020, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2020/12/16/buying-stuff-drives-climate-change/. ↩

90 Jörg Thomann, "Bücher über Fridays for Future: Gretarianer sind ziemlich anspruchsvolle junge Leute", FAZ.NET, 26 Jun 2020, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/buecher/rezensionen/sachbuch/zwei-neue-buecher-ueber-greta-thunberg-und-fridays-for-future-16812278.html. ↩

91 Maximilian König, "'Fridays for Future'-Studie: Sie sind jung und wollen was ändern", MAZ - Märkische Allgemeine, 26 Mar 2019, https://www.maz-online.de/Nachrichten/Politik/Fridays-for-Future-Studie-Sie-sind-jung-und-wollen-was-aendern. ↩

92 Jost de Moor Katrin Uba, Mattias Wahlström, Magnus Wennerhag and Michiel De Vydt, "Protest for a Future II: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays For Future Climate Protests on 20-27 September, 2019 in 19 Cities around the World", 2020, https://sh.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1397070&dswid=9234. ↩

93 This urgency is part of the reason why they argue that individual consumers' actions are not enough. Additionally, they see going beyond the individuals' responsibility as a matter of justice. Large-scale corporations, industry and individual, privileged consumers (some of whom are among the climate youth themselves) significantly contribute to global warming and have to be held accountable. Also see: Benjamin Bowman, "Fridays for Future: How the Young Climate Movement Has Grown since Greta Thunberg's Lone Protest", The Conversation, 28 Aug 2020, https://theconversation.com/fridays-for-future-how-the-young-climate-movement-has-grown-since-greta-thunbergs-lone-protest-144781. ↩

94 Garton Ash, et al., 20 Nov 2020. ↩

95 Ibid. ↩

96 Directorate-General for Communication, "Special Eurobarometer 501: Attitudes of European citizens towards the Environment", European Commission, Mar 2020, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2257_92_4_501_eng?locale=en. ↩

97 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Laura Nördstrom", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/interviewees/laura. ↩

98 Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture and Directorate-General for Communication, "Flash Eurobarometer 478: How do we build a stronger, more united Europe? The views of young people", European Commission, Apr 2019, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2224_478_eng?locale=en. ↩

99 Wouter Poortinga, Lorraine Whitmarsh, Linda Steg, Gisela Böhm and Stephen Fisher, "Climate Change Perceptions and Their Individual-Level Determinants: A Cross-European Analysis", Global Environmental Change 55 (March 2019): 25-35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.01.007. ↩

100 Matthew Ballew, Jennifer Marlon, Seth Rosenthal, Abel Gustavson, John Kotcher, Edward Maibach and Athnoy Leiserowitz, "Do Younger Generations Care More about Global Warming?", Yale University and George Mason University, New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 6 Nov 2019, https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/do-younger-generations-care-more-about-global-warming/. ↩

101 Garton Ash and Zimmermann, 6 May 2020. ↩

102 de Moor et al., "Protest for a Future II", 2020. ↩

103 The European Commission, "2030 Climate Target Plan", European Commission, 11 Sep 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/eu-climate-action/2030_ctp_en. ↩

104 Florence School of Regulation, "The European Green Deal", EUI: Florence School of Regulation, 19 May 2020, https://fsr.eui.eu/the-european-green-deal/. ↩

105 Kira Taylor, "EU agrees to set aside 37% of recovery fund for green transition", EURACTIV 29 Jan 2021 [18 Dec 2020], https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/eu-agrees-to-set-aside-37-of-recovery-fund-for-green-transition/. ↩

106 European Commission, "Financing the green transition: The European Green Deal Investment Plan and Just Transition Mechanism", European Commission, 14 Jan 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2020/01/14-01-2020-financing-the-green-transition-the-european-green-deal-investment-plan-and-just-transition-mechanism. ↩

107 EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. "Report on EU Green Bond Standard", June 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/190618-sustainable-finance-teg-report-green-bond-standard_en.pdf. ↩

108 European Commission, "EU taxonomy for sustainable activities", European Commission, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en. ↩

109 Frédéric Simon, "'Do No Harm': EU Recovery Fund Has Green Strings Attached, EURACTIV, 27 May 2020, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/do-no-harm-eu-recovery-fund-has-green-strings-attached/. ↩

110 Esther Snippe and Kira Taylor, "Concerns Raised over Green Spending as EU Moves Forward with Recovery Plan", EURACTIV, 17 Feb 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/concerns-raised-over-green-spending-as-eu-moves-forward-with-recovery-plan/. ↩

111 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Rafał Trzaskowski", europeanmoments.com, 2021, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/rafal-trzaskowski. ↩

112 European Commission, "Supporting climate action through the EU budget", European Commission, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/budget/mainstreaming_en; OEC Development Assistance Committee, "Rio Markers for Climate: Handbook", OECD, n.d., https://www.oecd.org/dac/environment-development/Revised%20climate%20marker%20handbook_FINAL.pdf. ↩

113 European Commission, "Guidance to member states - Recovery and resilience plans", European Commission, 17 Sep 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/3_en_document_travail_service_part1_v3_en_0.pdf; European Commission, "Supporting climate action through the EU budget", 2021. ↩

114 Romain Weikmans and J. Timmons Roberts, "The international climate finance accounting muddle: is there hope on the horizon?", Climate and Development 11, no. 2 (2019): 97-111, https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1410087; Wolfgang Münchau, "Beware of smoke and mirrors in the EU's recovery fund", Financial Times, 20 Sep 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/0ba23192-5f43-402d-8f26-6fce0ab669f3. ↩

115 European Commission, "Guidance to member states - Recovery and resilience plans", 2020. ↩

116 George Monbiot, "6. The problem seems to be that governments can hide behind the European Council and European Commission. On behalf of corporate lobbyists, they quietly push through policies they would never dare to propose at home", Tweet, @GeorgeMonbiot, 11 Mar 2021, https://twitter.com/GeorgeMonbiot/status/1370007716152934404. ↩

117 George Monbiot, "The shocking waste of cash even Leavers won't condemn", theguardian.com, 21 Jun 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/21/waste-cash-leavers-in-out-land-subsidie; George Monbiot, "4. The EU's Common Agricultural Policy, by far the biggest item in its budget, is one of the most destructive forces on Earth. The perverse incentives it creates have destroyed hundreds of thousands of hectares of prime habitat", Tweet, @GeorgeMonbiot, 11 Mar 2021, https://twitter.com/GeorgeMonbiot/status/1370007365232234497. ↩

118 Junge Grüne, "Klimaplan", Junge Grüne Schweiz, n.d., https://www.jungegruene.ch/klimaplan; Junge Grüne, "Massnahmenkatalog der Jungen Grünen Schweiz für Netto-Null Treibhausgasemissionen bis 2030", Junge Grüne Schweiz, n.d., https://data2.jungegruene.ch/userfiles/files/Junge%20Gru%CC%88ne%20Massnahmenkatalog%20-%20Netto%20Null%20Treibhausgasemissionen%202030(1).pdf; Garton Ash et al., 20 Nov 2020. ↩

119 Note that the most ambitious factions of the European Parliament, such as the Green Party faction, called for a 65% target. See Kate Abnett, "EU climate law talks dodge the 'elephant in the room'", Reuters, 2 Feb 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-eu-law-idUKKBN2A22KM; Elena Sánchez Nicolás, "EU Capitals Water down MEPs' Ambition in Climate Law", EUobserver, 3 Apr 2021, https://euobserver.com/green-deal/151117. ↩

120 Fréderic Simon and Kira Taylor, "Breakthrough as EU negotiators clinch deal on European climate law", EURACTIV, 21 Apr 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/climate-environment/news/breakthrough-as-eu-negotiators-clinch-deal-on-european-climate-law/. ↩

121 Greenpeace European Unit, "Why relying on offsets won't stop climate breakdown", Greenpeace, 23 Oct 2020, https://www.greenpeace.org/eu-unit/issues/climate-energy/45187/europe-cant-rely-on-nature-to-achieve-climate-objectives/; Umair Irfan, "Can you really negate your carbon emissions? Carbon offsets, explained", Vox, 27 Feb 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/2/27/20994118/carbon-offset-climate-change-net-zero-neutral-emissions. ↩

122 Elena Sánchez Nicolás, "EU Farming Deal Attacked by Green Groups", EUobserver, 22 Oct 2020, https://euobserver.com/green-deal/149826. ↩

123 Gerardo Fortuna, "Portuguese Presidency to Give MEPs a New Eco-Scheme Offer in CAP Talks", euractiv.com (blog), 21 Apr 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/portuguese-presidency-to-give-meps-a-new-eco-scheme-offer-in-cap-talks/. ↩

124 Franziska Tanneberger, Lea Appulo, Stefan Ewert, Sebastian Lakner, Niall Ó Brolcháin, Jan Peters and Wendelin Wichtmann, "The Power of Nature-Based Solutions: How Peatlands Can Help Us to Achieve Key EU Sustainability Objectives", Advanced Sustainable Systems 5, no. 1 (January 2021): 2000146, https://doi.org/10.1002/adsu.202000146; University of Leicester, "Drainage: A Key Concern for Tropical Peatlands", University of Leicester, n.d., https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/geography/research/projects/tropical-peatland/threats-to-tropical-peatlands. ↩

125 Note that a previous poll has already shown that Europeans are in support of restricting short-haul flights. However, our polling result is the first to find that they are willing to travel up to 12 hours instead (whereas previous estimates have been more conservative); Kim Willsher, "France to ban some domestic flights where train available", The Guardian, 12 Apr 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/apr/12/france-ban-some-domestic-flights-train-available-macron-climate-convention-mps. ↩

126 BBC News, "Climate change: Should you fly, drive or take the train?", BBC News, 24 Aug 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-49349566. ↩

127 Diana Ivanova and Richard Wood, "The Unequal Distribution of Household Carbon Footprints in Europe and Its Link to Sustainability", Global Sustainability 3 (2020): e18, https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.12. ↩

128 In our work with German high schools, the elimination of roaming fees across the EU was a frequently mentioned example of EU success and identification with the EU project. We attribute this to the fact that eliminating roaming charges requires a coordinated, cross-national effort, making it easier to be identified as an EU project. ↩

129 Daniel Judt, Reja Wyss and Antonia Zimmermann, "To save the EU, its leaders must first focus on saving the planet", The Guardian - This is Europe: European Opinion, 27 Jul 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2020/jul/27/europe-coronavirus-planet-climate. ↩