Democracy and the rule of law are at the very heart of the European Union. At the latest since the Maastricht Treaty, the EU has claimed to be not only an economic community, but also a community of values based on democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights. As a former professor of European politics at the University of Oxford put it in one of our expert interviews: “It is not only a matter of principle that European integration is only about bringing together states which are democratic, but it is also that you cannot have the economic relationship without the rule of law and democracy.”194 This chapter shows that young Europeans value the EU precisely because it champions these values within and beyond its borders. However, it also finds that the proportion of young Europeans who think that the EU symbolises democracy is decreasing.

The European Union has faced several challenges to democracy in recent years, be it the spread of disinformation undermining informed democratic participation, foreign electoral interference or the rise of populism across Europe. However, we argue that the most urgent and serious threat to democracy that the EU currently faces is that some of its member states have flagrantly and persistently undermined the EU’s fundamental values. The “constitutional revolution” taking place in Hungary since 2010 and the blatant attacks on judicial independence and the freedom of the press in Poland since 2015 gravely undermine the values on which the EU is based.195 This is especially urgent as the EU’s response has been notably weak in this respect. Compared to these authoritarian developments, the democratic shortcomings of the EU at the supranational level appear secondary.

In the following, we look at the state of democracy both at the supranational and member state levels and highlight what young Europeans expect from the EU, what the EU is currently saying and actually doing to strengthen and safeguard liberal democracy, and what we think the EU should do. We argue that democracy and the rule of law will not defend themselves but need defenders. Hence, we call on the EU to demonstrate that it will not tolerate any illiberal, semi-consolidated democracy in its community.

Before we turn to the expectation of young Europeans, we must define the key concepts of this chapter: democracy and the rule of law. When we talk about the rule of law in the EU, we refer to the democratic rule of law since democracy and the rule of law are, as Habermas famously put it, “co-original”.196 When speaking of democracy, we refer to liberal democracy, which is not just constituted by elections or the simple execution of the will of the majority, but by an effective system of checks and balances, free and fair elections, parliamentary opposition, an independent judiciary and protected fundamental rights allowing for the discursive exercise of liberal democracy. These fundamental principles can in turn only be safeguarded by the rule of law.

What young Europeans want EUrope to do

Building on the qualitative interviews we conducted with some 200 respondents and opinions we polled from a representative sample of EU citizens, we argue that young Europeans take the EU’s founding values—in particular democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights—for granted. The fact that the EU is a community of liberal democracies appears to be an underlying notion that is not really questioned any more. The overwhelming majority of Europeans (proportions ranging from 86% to 94%) think that key principles of the rule of law such as “the independence of judges”, “respect for and application of court rulings” and “acting on corruption” are important or essential.197

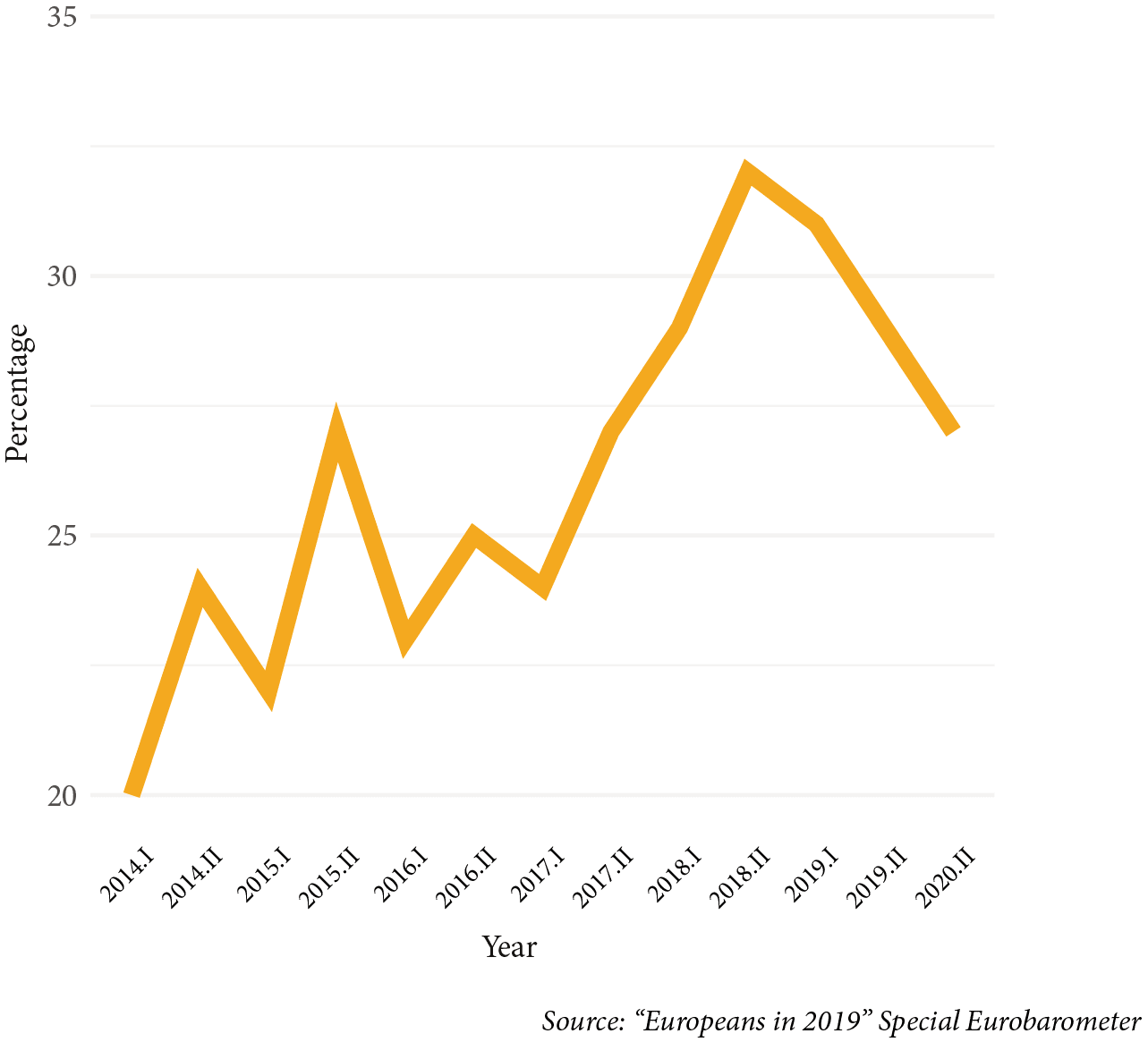

Young Europeans think that the EU’s protection of core values is one of its key advantages. Indeed, 30% of Europeans aged 15-24 believe that “the EU’s respect for democracy, human rights, and the rule of law” is the main asset of the EU—the top answer of a 2019 Special Eurobarometer polling. However, it appears that young Europeans have grown slightly disillusioned with the EU’s capacity and credibility to uphold its founding values.198 When asked what the EU symbolises for them personally, young Europeans chose ‘democracy’ in the early 2010s.199 However, this trend has reversed since the second half of 2018 (see Figure 18 below). Nevertheless, the percentage of young Europeans associating the EU with democracy has been consistently the highest among all age groups over the past decade.

On average, young Europeans are slightly less satisfied with the way democracy works in their country than at the EU level—a small difference of 3 percentage points (53%).200 However, Eurobarometer polls suggest that “political engagement tends to be felt on a general level, rather than differently in relation to different tiers or levels of governance.”201 Therefore, young Europeans’ concerns202 about European political processes may only be interpreted as general ones which transcend the national public sphere but most probably reflect their national impressions, given their limited knowledge of the EU and the lack of a meaningful European public sphere.

Hartwig Fischer, Director of the British Museum, argues in one of our expert interviews that the central task of the EU is to make it clear to all citizens what it really stands for: “The EU needs to make people understand what it is really about. It has not been very strong, it has not been very successful in making its members, all the citizens of the EU, really understand the values, the values the EU is based on, and the values it has created.”203

Figure 18

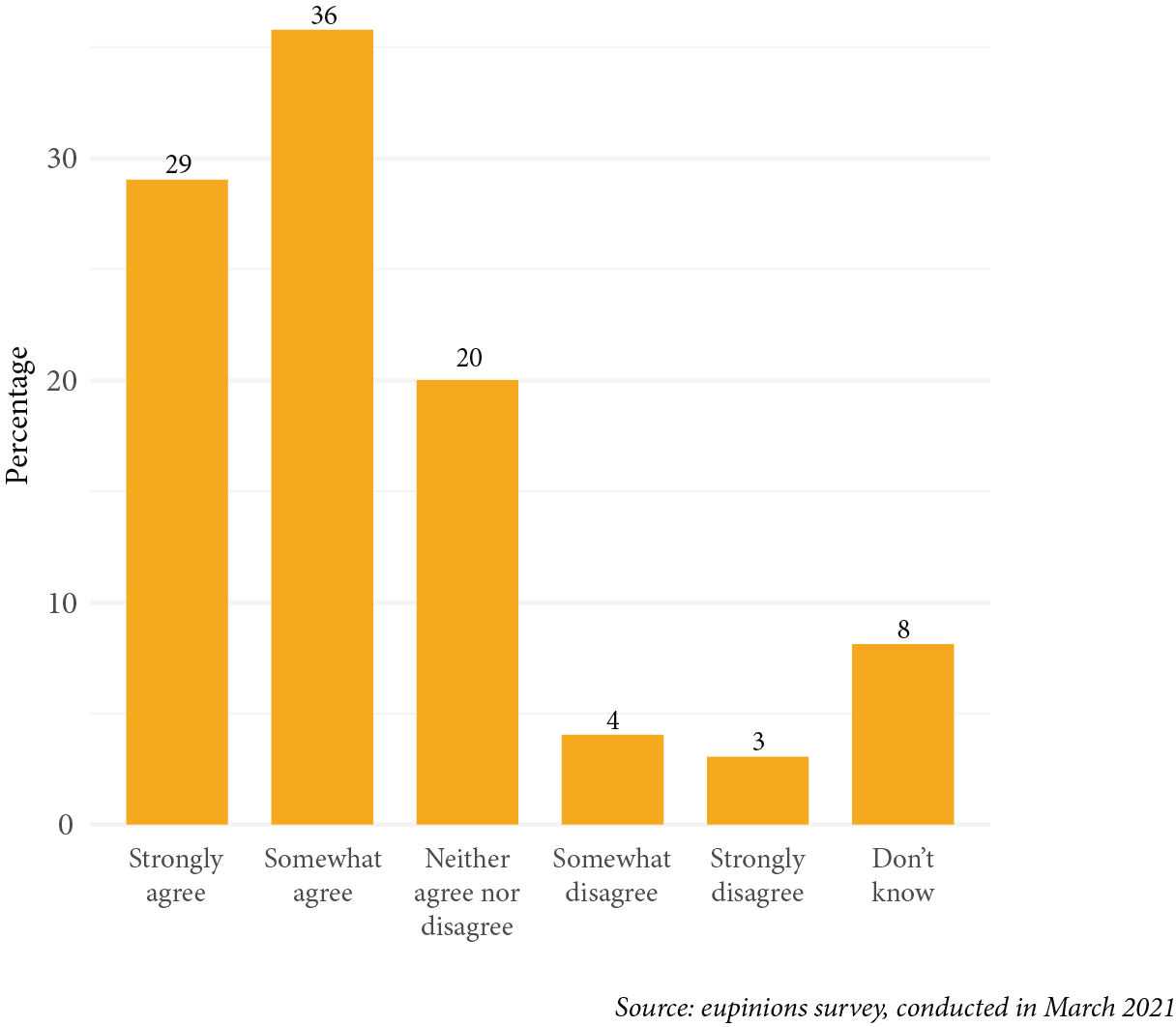

Young Europeans expect the EU to better communicate its fundamental values, but also to act upon them. Indeed, our March 2021 polling results show that a majority of Europeans (65%) believe that the EU should act more decisively to uphold liberal democratic institutions, such as independent courts and media, in all its member states (see Figure 19 below).204 Respondents from Germany (71%) and Poland (70%) were the most supportive. Interestingly, there were only small differences by age to this question, but larger disagreement by education: while 72% of university graduates agreed that the EU should take more decisive action, only 62% of non-graduates supported this.

In one of our expert interviews, Rafał Trzaskowski, Mayor of Warsaw, argues that the EU has to find new ways to uphold liberal democracy and the rule of law in its member states without punishing European citizens: “Why should we, local governments or the people, be penalised for the irresponsible behaviour of our government? Of course, we want the European Union to be tough, but I think that there are other ways to demonstrate to PiS [the Polish ruling party] that their behaviour will not be tolerated, by directly supporting independent local media, independent NGOs and independent local governments.”205

Figure 19

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement? "The EU should act more decisively to uphold liberal democratic institutions, such as independent courts and media, in all its member states."

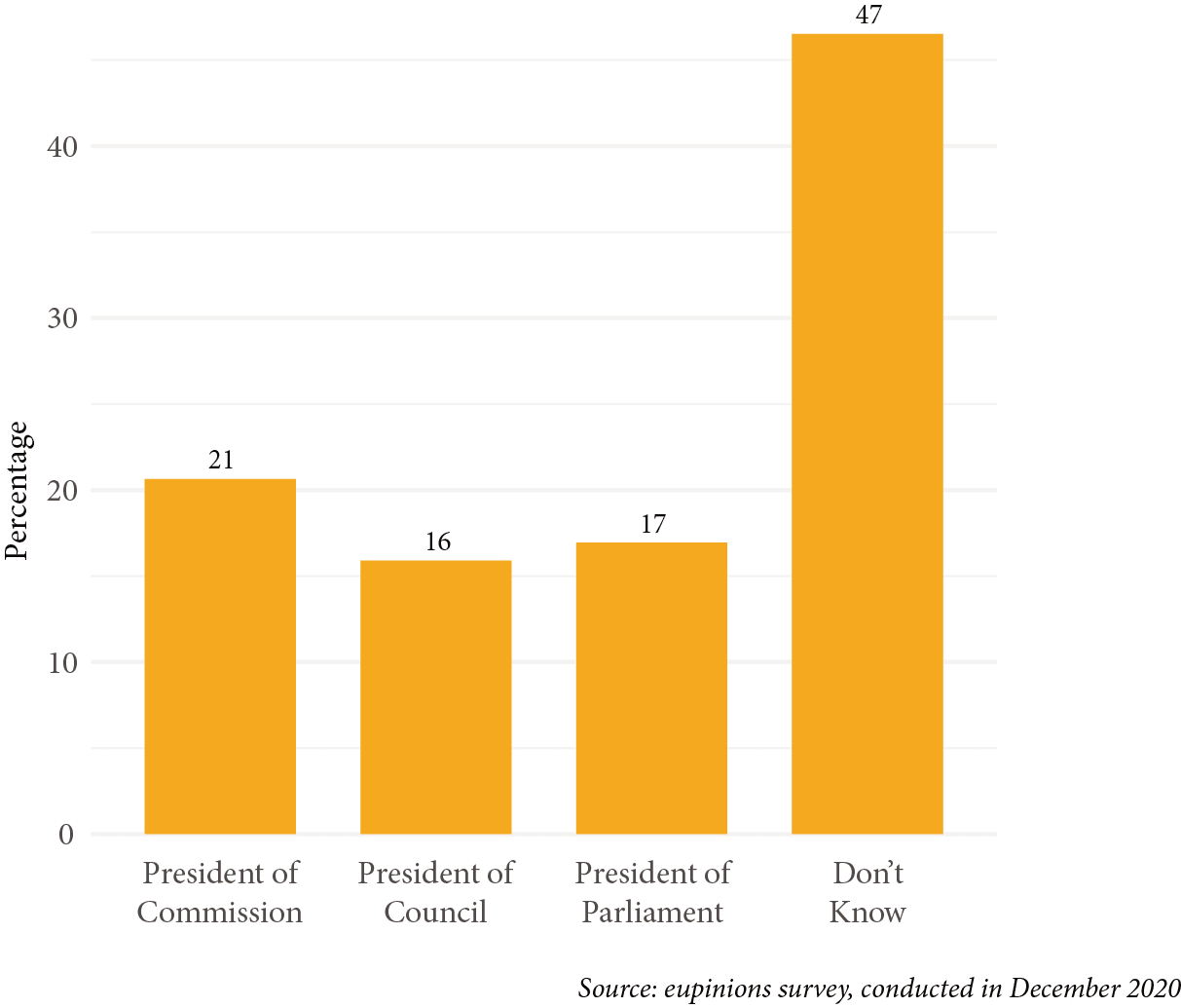

To be sure, most young Europeans are overall satisfied with the way democracy works in the EU (57%).206 However, their knowledge of democracy at the EU level is relatively limited. Nearly one in two young Europeans do not know that members of the European Parliament (EP) are directly elected by citizens of each member state.207 Similarly, only one in five respondents of our March 2021 survey with eupinions correctly identified the person who gives the EU’s State of the Union address—that is, the President of the European Commission (see Figure 20).208 How to explain that young Europeans highly value democracy and the rule of law but know so little about concrete democratic processes? We believe that young Europeans understand liberal democracy mainly as a set of values which they support and wish to see the EU uphold—more than as a specific set of political procedures and institutions.

Figure 20

Which senior EU figure gives an annual State of the Union address?

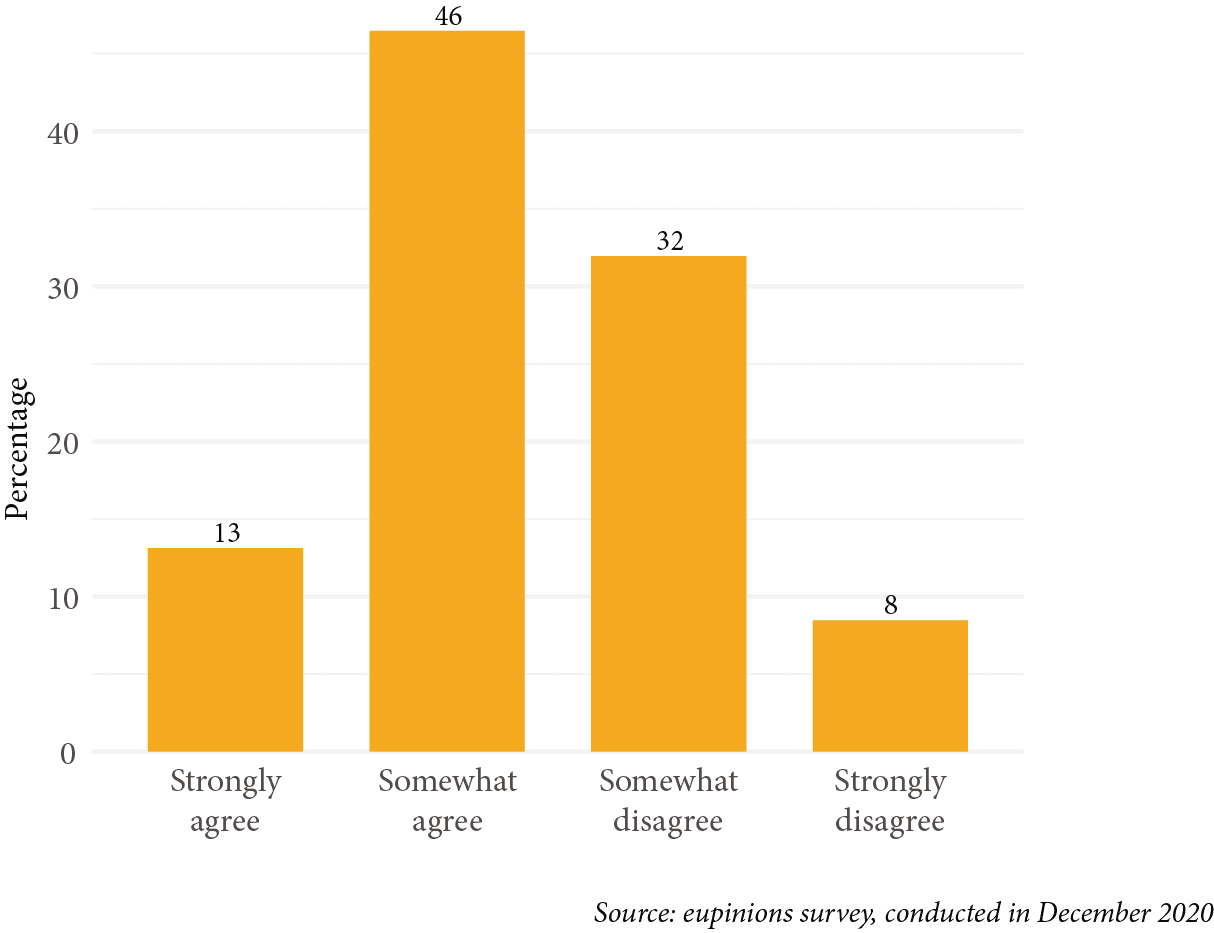

Younger generations tend to express their preferences and engage with political life differently, compared to older European citizens. Voting is the primary means of political expression, but the majority of young Europeans do not vote for MEPs (58%), and our March 2021 poll revealed that they believe that the presence of the European Parliament is of secondary importance to delivering effective action (59%) (see Figure 21).209 They think more decisions should be taken at the EU level (61%) and they want more action, especially when it comes to urgent matters such as climate change.210 However, they do not believe that their preferences for such actions are best communicated through voting for parliamentarians in Brussels who they have never met or even heard of, albeit that being the principal channel of direct representation available to them. In fact, most do not even understand the European Parliament’s role in the adoption of new laws. As a result, they tend to value policy outputs more than political procedures, as strikingly illustrated by our March 2021 poll showing that 53% of young Europeans think that authoritarian states are better equipped than democracies to tackle the climate crisis.211

Figure 21

"As long as the EU delivers effective action, the presence or absence of the European Parliament is of secondary importance."

In sum, as already suggested in this report, young Europeans appear more concerned about what scholars call ‘performance legitimacy’—legitimacy driven by policy outputs—than ‘procedural legitimacy’—legitimacy driven by the nature of policy making processes. However, we argue that this apparent disinterest in and contempt for democratic processes is precisely generated because such processes are currently not appealing nor adapted to Europe’s youth. Young Europeans are interested in an EU that delivers effective action, and they wish to make their voices heard through alternative means rather than European Parliament elections. They wish to see democracy being more deliberative, direct and involving more ordinary people as representatives. This directly points to the importance of the recently launched Conference on the Future of Europe, which we address further below. In the longer term, it also calls for rethinking the ways in which the EU engages with its young citizens in political discussions, one that does not only consist of parliamentary elections and ad hoc bottom-up conferences. As put by John Keane in Democracy and Media Decadence: “Democracy is coming to mean much more than free and fair elections, although nothing less.”212

What the EU is doing and is not doing

In the 1950s, the European Communities were established as an economic project to foster economic cooperation and to preserve and strengthen peace and liberty after the Second World War. Even if the European Communities were not explicitly founded on democracy and liberalism, the Union undoubtedly evolved as a community of liberal democracies.213 Nevertheless, it was not until 1993, when the Copenhagen criteria were defined, that norms relating to liberal democracy explicitly became part of the EU’s accession criteria. The Treaty of Amsterdam (1997) then enshrined for the first time the fundamental ‘principles’ on which the EU is based. Their status was further strengthened by the Treaty of Lisbon (2007) which refers to the fundamental ‘principles’ now as founding ‘values’. Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), one of the two Treaties forming the constitutional basis of the EU, thus reads as follows: “The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities.”

The rule of law, democracy and fundamental rights are considered the “true ‘constitutional’ principles of the EU”.214 Since democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights are at the very heart of the European idea, the EU promises to promote (Article 3 TEU) and to protect these founding values through various instruments. However, especially in the case of Hungary and Poland, the EU has been criticised for not being able to prevent democratic backsliding and protect liberal democracy. In this section, we will therefore argue that there is a significant gap between what the EU says it is doing, is actually doing, and is not doing to uphold and strengthen democracy in its member states.

In her agenda for Europe, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen explicitly placed “a new push for European democracy” as one of the six ‘headline ambitions’ that would shape the Commission’s work programme for the years 2019 to 2024.215 By putting emphasis on a more transparent and more inclusive decision-making process, the Commission seems to have heard young Europeans’ calls for more participation and seeks to bring the EU closer to its citizens. Specifically, the Commission aims at giving EU citizens a greater role in decision-making and enhancing the accountability of EU representatives. The Commission President has, for example, indicated her willingness to support a “right of initiative” for the EU Parliament and “to move towards full co-decision power for the European Parliament and away from unanimity for climate, energy, social and taxation policies”.216 Moreover, von der Leyen has stated her intention to revise the Spitzenkandidaten system and possibly introduce transnational lists in the European elections in order to increase the visibility of European politics.217 During her presidency so far, however, little progress has been made in these regards. While the Commission seems committed to its goal of more democratic and efficient action at the European level, it has not yet delivered on these promises, hiding behind the unforeseen Covid-19 pandemic crisis.

High hopes were originally placed on the Conference on the Future of Europe which was launched on 9 May 2021 and is set to reach conclusions within 15 months.218 But whether the conference will become a “game changer” that also drives and promotes more citizen participation in the EU may well be doubted. The Conference on the Future of Europe was originally considered as a unique opportunity for the EU to re- engage with its young citizens and to “bring together citizens, [...] civil society and European institutions as equal partners”.219 However, so far, the envisaged conference has made headlines mostly for delays, internal disputes over who should become its president, and doubts about whether there is enough time and willingness to really achieve meaningful results.220 Moreover, the Conference faced considerable criticism for its top-down approach and disagreements among member states concerning the legitimacy of the Conference’s outcomes.221 In sum, the Conference on the Future of Europe had already degenerated into an institutional turf war before it even began. Its original ambitious agenda of grassroots engagement with Europe’s youth and civil society has been replaced by a bureaucratic organisation under male-dominated leadership of officials wary to bring up the subject of treaty changes. Not surprisingly, 48% of EU citizens say that they are personally unwilling to take part in the event.222 So, it seems like the EU missed another chance to engage with its (young) citizens.

In the remainder of this section, we would like to highlight what the EU says it is doing and is actually doing with regard to the systematic and persistent violations of the EU’s fundamental values in some of its member states. The EU’s response can be summarised as follows: It has done too little, reacted too late, and proceeded too weakly against violations of liberal democracy and the rule of law in its member states.223

As the “guardian of the treaties”, the Commission has put great emphasis in its political guidelines on defending the rule of law, and has reiterated time and again that “breaches of the rule of law cannot be tolerated” and “European values are not for sale.”224 However, the Commission (and the EU in general) has rarely gone beyond this lip service. In her first State of the Union speech, President von der Leyen claimed that “the Commission attaches the highest importance to the rule of law.”225 But in the same speech, she painted a picture which seemed “distressingly detached from reality”226 by lauding the new ‘Annual Rule of Law Report’ as a “starting point” to ensure that “there is no backsliding” in the EU.227 Several leading academics and

political commentators have pointed out that speaking of a starting point is preposterous when one considers the numerous breaches of the EU’s founding values by the Hungarian and Polish governments.228 Freedom House has downgraded Poland to a semi-consolidated democracy, and Hungary is no longer classified as a democracy at all.229 It is worth mentioning that violations of the rule of law can be observed not only in Hungary and Poland but also in other European countries. We do not claim that all is well in other European democracies but “[t]hey have not been captured by single parties trying to remould the entire political system in their favour, as has been the case in Hungary” (and now also Poland).230 Therefore, special attention is paid to these two most serious cases of democratic backsliding.

It may well be that the new Annual Rule of Law Report, which assesses the situation of the rule of law in all member states and aims to identify rule of law problems early on proves to be a successful tool to detect anti-democratic reforms in countries where illiberal tendencies are beginning to unfold, but it is unlikely that this report actually helps to stop or reverse democratic backsliding in the case of Hungary or Poland. Against this backdrop, Daniel Kelemen, professor of political science and law at Rutgers University, aptly stated that “[y]ou can’t fight autocracy with toothless reports.”231

The EU has three main mechanisms at its disposal to protect the rule of law and liberal democracy in its member states: the Rule of Law Framework, infringement procedures, and the Article 7 procedure.232 In the case of Poland, the European Commission brought infringement proceedings before the European Court of Justice, made recommendations under the Rule of Law Framework, and triggered Article 7(1). In this section, we will focus mainly on the latter two mechanisms. The Rule of Law Framework was activated for the first time with respect to Poland in 2016. This procedure seeks to address systemic threats to the rule of law early on and to prevent the activation of Article 7 by recommending early intervention measures. In the case of Poland, this procedure overall proved to be ineffective. The Commission opened a ‘structured dialogue’ with the Polish government and issued several recommendations, but the Polish government clearly disagreed with the Commission’s positions and rejected its recommendations. As the Polish government continued to seriously and continuously violate the EU’s fundamental values, the Commission initiated the Article 7 procedure against Poland on 20 December 2017. This seeks to determine whether there is a clear risk of a serious breach of the values the EU is founded on. Given the lack of progress in the Polish case, the rule of law framework was never even applied to Hungary. In the case of Hungary, the Commission initiated infringement proceedings, but for a very long time it did not take any meaningful political action against the dismantling of democracy; instead, it relied on appeasement. It was then the European Parliament that triggered Article 7.

Consequently, both Hungary and Poland are currently subject to the preventive arm of the Article 7 procedure. In general, this procedure aims to ensure that all member states respect the EU’s founding values and theoretically provides the option to suspend the membership rights of a ‘rogue’ state (due to the required unanimity, however, this last-resort measure is almost impossible). Both academics and the European Parliament have condemned the Council’s inaction with regard to the Article 7 procedure and further criticised that the few hearings that have taken place have not been organised in a regular, structured and transparent manner.233 Also, documents relating to the procedure are not systematically made available to the public. In January 2020, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the ongoing hearings, taking to task the Council (and thus the member states) in an unusually direct way: “The failure by the Council to make effective use of Article 7 continues to undermine the integrity of common European values, mutual trust and the credibility of the European Union as a whole.”234 Furthermore, the European Parliament notes that, according to numerous sources, the situation on the ground in both Poland and Hungary has deteriorated since the Article 7 proceedings were triggered.235 In one of our expert interviews, Rafał Trzaskowski, the current Mayor of Warsaw, echoes this: “Let’s put it bluntly, Article 7 is not very effective, and we knew it all along.”236 In sum, it must be said that the EU’s most powerful tool (at least on paper) was both triggered too late and is now not being used to the extent that it could be.

Since the beginning of 2021 the EU has another—long-awaited—tool in its toolbox to protect liberal democracy and the rule of law: the rule of law conditionality mechanism which aims to protect the EU budget from governments that violate rule of law standards. For years, many have argued that the only measure that could keep the Hungarian and Polish governments from further eroding the rule of law and democracy would be to make the distribution of EU funds conditional on compliance with the EU’s founding values. Both Hungary and Poland expressed fundamental objections to such a conditionality mechanism and in return threatened to veto the EU budget and post-Covid-19 recovery fund. To overcome the threatened Polish and Hungarian veto, the European Council watered down the mechanism and negotiated a compromise in December 2020. This conceded to Hungary and Poland that the enforcement of the Conditionality Regulation would be delayed until the European Court of Justice issues a ruling on its legality. The new Conditionality Regulation, also known as the “Rule of Law Conditionality Mechanism”, which came into force on 1 January 2021, provides that the Commission can propose to trigger the mechanism against an EU government—but only after detecting a breach of the principles of the rule of law that affects the financial management of the EU budget or the protection of the financial interests of the EU “in a sufficiently direct way”. The Council then has one month to vote by qualified majority on the proposed measures. Subsequently, payments to the errant member state from the EU budget can be reduced or frozen.

Leading academics argue (see our webinar on “Is there still ‘rule of law’ in Hungary and Poland”) that the European Council conclusions, while not formally binding, cast a long shadow over the Conditionality Regulation, making it virtually useless and thus “undermining the rule of law on all fronts.”237 The final regulation sounds more like the EU wants to defend its budget rather than the rule of law and liberal democracy. The Commission can only intervene if the financial interests of the Union are at risk. However, it may not do so if the violation of the EU’s fundamental values does not affect the Union’s financial or budgetary interests. In addition, it has been pointed out that the EU already possesses means (the Common Provisions Regulation) to suspend the flow of funds to backsliding states in which the rule of law is systematically violated, but that “[t]he real problem to date has not been the lack of adequate legal tools, but the lack of political will on the part of the European Commission to use the tools that already exist.”238

The Commission has certainly not sufficiently fulfilled its duty as “guardian of the treaties”. Still, we would like to point out that protecting the EU’s fundamental values is a shared responsibility. When we talk about the EU’s response to democratic backsliding, we must also call other member states as well as political parties to account. To date, most states have remained largely silent and exerted little pressure on the rogue states in their midst. In the European Parliament, the European People’s Party (EPP) has long held a protective hand over Orbán’s Fidesz party. Even if it is a partial success that Fidesz has now left the EPP (when its expulsion was imminent), this comes far too late. In sum, there is a significant gap between what the EU says and what it actually does when it comes to safeguarding the rule of law and liberal democracy in its member states.

What we think the EU should do

Building on young Europeans’ expectations and the EU’s current actions related to democracy and the rule of law, in this section we will present recommendations on the Conference on the Future of Europe, democracy at the EU level and safeguarding democracy at the member state level.

We think that the Conference on the Future of Europe, as it is currently agreed and planned to unfold, risks being a highly disappointing top-down bureaucratic exercise. Its organisation accentuates the belief of young Europeans that the EU is a complex, top-down structured set of institutions in which their voices are not sufficiently heard. The Conference on the Future of Europe should adopt a truly bottom-up approach directly involving EU citizens, in particular youth and civil society, in order to have its intended impact. We believe that the original intention of the Conference could be reinstated through a central role for civil society organisations, which currently are marginalised. Second, it should feature more inclusive, non-standard, digital forms of public participation and democracy in order to generate meaningful discussions with Europeans.239 Third, its leading figures should be accompanied by young European citizens and its organisation should emphasise transparency in order to reflect young Europeans’ concerns. In the future, we suggest festival-like events that travel across Europe with a strong and forward-looking presence on social media. This set-up would approach new audiences to be reached beyond the usual pro-European suspects. Finally, treaty changes have been clearly sidelined for the moment, but the discussion should remain open and prepare for further arising needs to redirect the constitutional course of the EU. It would be foolish to suppress the need for conversation about treaty revisions that has arisen from European citizens themselves.

At the EU level, we believe that more support should be provided for pan-European initiatives that nurture a “European public sphere” in order to encourage more grassroot discussions about democracy in Europe. Public spheres must be connected not only supranationally (at the EU level) but also trans-nationally (between member states). With this in mind, building on the DiscoverEU programme, an interrail pass should be given to every EU citizen turning 16 without an application process, valid for five years within the European Union. Media initiatives breaking language barriers such as Forum.eu should be further encouraged. The different national perspectives on European history, philosophy, politics and economy should be better integrated in school curricula, which currently widely vary across the continent. As explained by a professor of interlinguistics, “[i]t’s not neutral. If you study history in English you have the English point of view. If you study that in Dutch you have the Dutch point of view, that’s very different.”240

Furthermore, civic education and media literacy should be included in the programme of all schools across Europe in order to foster critical democratic thinking and a better understanding of the EU, as well as to debunk the often simplistic arguments of populists. In his Eight Remarks on Populism, Ralf Dahrendorf stated: “Populism is easy, democracy is complex. [...] Learning to live with complexity may be the most significant task of democratic civic education.”241 Strategic communication should thus be a priority for the EU, not only in its foreign but also internal policies. Additionally, the EU should substantially boost the Erasmus+ programme as its activities clearly accelerate citizens’ identification with the EU and sharpen their interest and participation in democratic activities. It should be better promoted within the EU, particularly among educationally disadvantaged groups and early on in the educational system. Initiatives that allow for the exchanges of teachers and inter- school collaboration should also be given more attention. Finally, it should include further opportunities for direct connection and debate at the local level, similarly to initiatives led in the EU’s neighbourhood such as the Young European Ambassadors.

A central question remains: What do we want the EU to do about its most pressing democratic threat—democratic backsliding in its member states? First of all, we would like European officials to stop talking only about a “rule of law crisis” when it is actually liberal democracy that is under attack. The EU has framed most of its activities as measures to “protect the rule of law”. Undoubtedly, the rule of law is being violated in some of its member states—notably in Poland and Hungary. However, we agree with Jan-Werner Müller that the “virtually exclusive emphasis on rule of law in public discourse has, arguably, reinforced the sense that Europe only cares about liberalism, while the nation-state does democracy.”242 Therefore, the EU needs to make clear that it stands up for democracy and safeguards free and fair elections, freedom of expression (including media and academic freedom), freedom of association, and human rights in its member states.

At this point, we call on the European Union to protect democracy from illiberalism in Hungary and Poland. We firmly believe that “illiberal democracy” is a contradiction in terms and opposed to the founding values of the EU. As we have seen in the previous section, the European Union has a rich toolbox to safeguard liberal democracy and the rule of law. We believe that it is high time that the EU finally uses these instruments properly and backs up its words with deeds.

We would like the Council to resume organising hearings under the Article 7 procedure and conduct those in a regular, structured and public manner. The Article 7 procedure is often wrongly considered as the EU’s “nuclear option”.243 However, the preventive arm of this procedure (Art. 7(1) TEU), to which both Poland and Hungary are subject, is anything but “nuclear”—its means are warnings, dialogue and recommendations, not sanctions.244 Therefore, we see no reason why the Council should not proceed with the hearings and exert public pressure on the Hungarian and Polish governments.

We call on the European Commission to make use of the new rule of law conditionality mechanism in a timely manner and not to wait for the ECJ’s ruling on this issue. Given that the Hungarian and Polish governments are obviously trying to stall for time, the Commission must be careful not to make the same mistake again and apply its instruments only when it is already too late, as happened with the Article 7 procedure. Furthermore, we hope that the European Commission will interpret the new rule of law conditionality broadly and use it not only to protect the EU budget from rule of law violations but also to protect liberal democracy.

We call on other member states and major groups in the European Parliament to take a clear stance on the erosion of democracy in member states. Both Fidesz and PiS (i.e., the ruling parties in Hungary and Poland) should be politically shunned and their violations of the rule of law and democratic values condemned. We expect member states to finally take their responsibility and put pressure on backsliding member states, be it through embassies, “naming and shaming”, or through legal actions. Given the severity of violations in Hungary and Poland, member states should finally make use of Article 259 of the Treaty of the European Union which allows them to sue another member state which “has failed to fulfil an obligation under the Treaties” before the Court of Justice of the European Union.245 In this regard, we welcome the resolution of the Dutch Parliament urging the Dutch government— instead of waiting any longer for the Commission—to take Poland to the ECJ.

In addition to these recommendations, which relate to tools already available, we have two further recommendations for new policies. Firstly, we believe that the EU should create a substantial EU fund for the defence of media freedom across the continent. Thus, we welcome current discussions of a European Media Freedom Act. Secondly, we call on the EU to allocate funding from the EU recovery fund directly to regional and local governments to avoid them being dependent on the goodwill of central governments. Bypassing national governments by allocating EU funds directly to municipalities should help to empower Warsaw and Budapest, and thus to strengthen the democratic opposition in Hungary and Poland. This could help to punish the Hungarian government, without hurting Hungarians.

To sum up, we expect much clearer action from the EU showing that it does not tolerate any illiberal, semi-consolidated democracy in its community. Many tools are already available; now is the time to use them. Especially after the Covid-19 pandemic, European citizens seem ready for change more than ever. Democracy and the rule of law will not defend themselves, they need defenders. We have shown that young Europeans value the EU precisely because it champions the rule of law, liberal democracy, and human rights within and beyond its borders. It is now up to the European Union to ensure that the “community of values” does not degenerate into an empty phrase.

194 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Jan Zielonka", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/jan-zielonka. ↩

195 In its Nations in Transit report, Freedom House downgraded Poland to a semi-consolidated democracy, and Hungary is no longer classified as a democracy at all (Freedom House, "Nations in Transit 2021", Freedom House, 2021, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/NIT_2021_final_042321.pdf.) ↩

196 Jürgen Habermas, Die Einbeziehung des anderen. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1996, 299; This is in line with the European Commission's understanding, which blends the concept of the rule of law with democracy and fundamental rights. (e.g., European Commission, "Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council. Further strengthening the Rule of Law within the Union State of play and possible next steps", Brussels, European Commission, 3 Apr 2019, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0163&from=EN.) ↩

197 Directorate-General for Communication, "Special Eurobarometer 489: Rule of Law in the European Union", European Commission, Apr 2019, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2235_91_3_489_eng?locale=en. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2235. ↩

198 Younger generations' increasing dissatisfaction with democracy has also been observed at the global level (R.S. Foa, A. Klassen, D. Wenger, A. Rand and M. Slade, "Youth and Satisfaction with Democracy: Reversing the Democratic Disconnect?" Cambridge, United Kingdom: Centre for the Future of Democracy, Oct 2020, https://www.cam.ac.uk/system/files/youth_and_satisfaction_with_democracy.pdf.) ↩

199 Directorate-General for Communication, "Special Eurobarometer 486: Europeans in 2019", European Commission, Mar 2019, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2225_91_2_486_eng?locale=en. ↩

200 Ibid. ↩

201 Directorate-General for Communication, "Parlemeter 2020: A Glimpse of Certainty in Uncertain Times", European Parliament, Feb 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2020/parlemeter-2020/en-report.pdf, 41. ↩

202 Across all age groups, Europeans' main concerns related to democracy and elections are social networks' lack of transparency in political advertisements, election (cyber-)manipulation, as well as online disinformation and misinformation (Directorate-General for Communication, "Special Eurobarometer 477: Democracy and elections", European Commission, Nov 2018, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2198_90_1_477_eng?locale=en). When it comes to the Rule of Law, Europeans believe that the top three points which need improvement are making decisions in the public interest, codes of ethics for politicians and acting on corruption (DG COMM, "Special Eurobarometer 489: Rule of Law in the European Union"). Finally, 54% of young Europeans agree that "The rise of political parties protesting against the traditional political elites in various European countries is a matter of concern" (DG COMM, "Special Eurobarometer 486: Europeans in 2019"). ↩

203 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Hartwig Fischer", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/hartwig-fischer. ↩

204 Garton Ash et al., 25 May 2021. ↩

205 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Rafał Trzaskowski", europeanmoments.com, 2020, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/rafal-trzaskowski. ↩

206 DG COMM, "Special Eurobarometer 486: Europeans in 2019". ↩

207 Ibid. ↩

208 Garton Ash et al., 26 Jan 2021. ↩

209 Directorate-General for Communication, "The 2019 Post-Electoral Survey", European Parliament, Sep 2019, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2019/post-election-survey-2019-complete-results/report/en-post-election-survey-2019-report.pdf; Garton Ash et al., 26 Jan 2021. ↩

210 DG COMM, "Special Eurobarometer 486: Europeans in 2019". ↩

211 Garton Ash and Zimmermann, 6 May 2020. ↩

212 John Keane, Democracy and Media Decadence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 80. ↩

213 When in 1961 an authoritarian regime (Spain under Franco) wanted to join the Community, the European Parliamentary Assembly clearly expressed its resistance and outlined that "the guaranteed existence of a democratic form of state, in the sense of a free political order, is a condition for membership" (European Parliamentary Assembly, "Question Orale Sur L'ouverture De Négociations Avec L'espagne", 1962: 81-84.) On the development of the European Union as a "community of values" and the role that liberal democratic values already played in the early years of European integration, see Kiran Klaus Patel, Project Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 200, 146-175. ↩

214 Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs, "The EU framework for enforcing the respect of the rule of law and the Union's fundamental principles and values", European Parliament, Jan 2019: 8, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/608856/IPOL_STU(2019)608856_EN.pdf. ↩

215 Ursula von der Leyen, "A Union that strives for more. My agenda for Europe", European Commission, 2019. ↩

216 Ibid. ↩

217 Ibid. ↩

218 Maia de la Baume, "EU finally approves Conference on the Future of Europe", Politico, 10 Mar 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-leaders-eu-sign-off-conference-on-the-future-of-europe/. ↩

219 von der Leyen, "A Union that strives for more". ↩

220 see e.g., Mehreen Kahn, "Conference on the Future of Europe risks becoming an orphan project", Financial Times, 1 Mar 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/d2e27ae6-9094-424c-9786-768d767ccfb6; Mehreen Kahn and David Hindley, "Talking shop at the Conference on the Future of Europe", Financial Times, 10 Mar 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/231dcda1-69c9-45e7-a0c4-7e243212209e. ↩

221 see e.g., Alberto Alemanno, "Let civil society have its say!", Voxeurop, 1 Feb 2021, https://voxeurop.eu/en/let-civil-society-have-its-say/; Reneta Shipkova, "Conference on the Future of Europe. Five reasons for moderate pessimism", Friends of Europe, 3 Mar 2021, https://www.friendsofeurope.org/insights/conference-on-the-future-of-europe-five-reasons-for-moderate-pessimism/. ↩

222 Directorate-General for Communication, "Special Eurobarometer 500: Future of Europe", European Commission and European Parliament, Mar 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2021/future-of-europe-2021/en-results-annex.pdf. ↩

223 e.g., Daniel Kelemen and Kim Lane Scheppele, "How to Stop Funding Autocracy in the EU", Verfassungsblog, 10 Sept 2018, https://verfassungsblog.de/how-to-stop-funding-autocracy-in-the-eu/. ↩

224 Ursula von der Leyen, "State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen", European Commission, 16 Sep 2020. ↩

225 Ibid. ↩

226 Daniel Kelemen, "You can't fight autocracy with toothless reports", EU Law Live, 6 Oct 2020, https://eulawlive.com/op-ed-you-cant-fight-autocracy-with-toothless-reports-by-roger-daniel-kelemen/. ↩

227 von der Leyen, "State of the Union Address". ↩

228 E.g., Kelemen, "You can't fight autocracy with toothless reports". ↩

229 Freedom House, "Nations in Transit 2020". ↩

230 Jan-Werner Müller, What is Populism?, London: Penguin Books, 2017, 59. ↩

231 Ibid. ↩

232 Besides these three main mechanisms, the EU has further instruments to protect and promote its founding values, such as the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (included in the Act of Accession for Bulgaria and Romania), the EU Anti-Corruption Report, the Justice Scoreboard, or the EU's inter- institutional annual reporting on fundamental rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. ↩

233 E.g., Laurent Pech, "From 'Nuclear Option' to Damp Squib?: A Critical Assessment of the Four Article 7(1) TEU Hearings to Date", Verfassungsblog, 13 Nov 2019, https://verfassungsblog.de/from-nuclear-option-to-damp-squib/; European Parliament, "Ongoing hearings under article 7(1) of the TEU regarding Poland and Hungary", 16 Jan 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0014_EN.html. ↩

234 Ibid. ↩

235 E.g., Laurent Pech, Patryk Wachowiec and Dariusz Mazur, "1825 Days Later: The End of the Rule of Law in Poland (Part I)", Verfassungsblog, 13 Jan 2021, https://verfassungsblog.de/1825-days-later-the-end-of-the-rule-of-law-in-poland-part-i/. ↩

236 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Rafał Trzaskowski", europeanmoments.com, 2021, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/rafal-trzaskowski. ↩

237 Europe's Stories, "Is there still 'rule of law' in Hungary and Poland?'", europeanmoments.com, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=T4T742riM-A&t=4s; Kim Lane Scheppele, Laurent Pech and Sébastien Platon, "Compromising the Rule of Law while Compromising on the Rule of Law", Verfassungsblog, 13 Dec 2020, https://verfassungsblog.de/compromising-the-rule-of-law-while-compromising-on-the-rule-of-law/. ↩

238 Kelemen and Scheppele, "How to Stop Funding Autocracy in the EU". ↩

239 Keane conceptualises this idea as "monitory democracy", which he defines as a form of democracy in which "potentially all fields of social and political life come to be publicly scrutinised, not just by the standard machinery of representative democracy, but by a whole host of non-party, extra-parliamentary and often unelected bodies operating within, underneath and beyond the boundaries of territorial states. [...] it is as if the principles of representative democracy - public openness, citizens' equality, selecting representatives - are superimposed on representative democracy itself " ( Keane, Democracy and Media Decadence). ↩

240 Europe's Stories, "Interview with Federico Gobbo", europeanmoments.com, 2021, https://europeanmoments.com/stories/federico-gobbo. ↩

241 Ralf Dahrendorf, Eight Remarks on Populism, 2003: 16. ↩

242 Müller, What is Populism?, 58-59. ↩

243 José Manuel Barroso, "State of the Union address 2013", European Commission, 2013. ↩

244 Kim Lane Scheppele and Laurent Pech, "Is Article 7 really the EU's 'Nuclear Option?', Verfassungsblog, 6 Mar 2018, https://verfassungsblog.de/is-article-7-really-the-eus-nuclear-option/. ↩

245 Dimitry Kochenov, "Biting Intergovernmentalism: the case for the reinvention of article 259 TFEU to make it a viable rule of law enforcement tool", The Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 7, no. 2, (2015): 153-174, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-015-0019-1. ↩