2023 Dahrendorf Colloquium - Europe and Freedom

by Josef Lolacher

Regardless of which concept of freedom is used as a basis, most people are likely to agree that it is not enough to simply determine whether a person is free or not. Instead, we want to know to what degree a person is free, how free they are in comparison to others, and what they are free to do. In other words, we want to distinguish not only between the presence or absence of the quality of freedom, but also between the various degrees and forms to which it is present. This applies not only to individual persons, but also to entire societies and countries.

As Thomas Hobbes famously stated in his Leviathan: “Liberty is in some places more, and in some less, and in some times more, in other times less, according as they that have the sovereignty shall think most convenient”.1 Ian Carter takes up this thought and asks, “but where and when has liberty been ‘more’, and where and when has it been ‘less’?”2. Political thinkers have grappled with this question for decades, if not centuries, putting forward competing and not seldom opposing views. While Roger Scruton, for example, believes that it is in Great Britain that we find, “more freedom … of every kind than in most other countries of the world”3, his compatriot Bryan Magee points to the United States, claiming that “there is more freedom for the individual there than here”4. The state of California, in particular, appears to be the epitome of freedom for him: “There can be few more attractive places to live in, and few where the individual is freer to do his own thing”5. Yet, all over America, he explains, people are “extraordinarily free”. This is in stark contrast to Christopher Caudwell, who, as a Marxist, strongly believes “as Russia shows, even in the dictatorship of the proletariat, man is already freer”6. According to John Somerville, we should at least note that “in the communist world, there is more freedom from the power of private money, from the influence of religious institutions, and from periodic unemployment”7. Although it may be the case that capitalism makes some people poorer, this is not enough to convince Friedrich von Hayek that it makes them less free. He argues that even “the poor in a competitive society” are “much more free than a person commanding much greater material comfort in a different type of society”8. Despite these pronounced differences, virtually all of these views share an implicit or explicit understanding of freedom as a quantitative attribute that allows us to make meaningful statements about how free a person or society is relative to others. Freedom is thus understood as an attribute that is not merely possessed or lacked but possessed or lacked to a certain degree9. This implies that freedom should, at least in principle, be quantifiable and measurable.

Our understanding of freedom as a measurable quality is primarily based on Gerald MacCallum’s conception of freedom as the absence of preventing conditions on agents’ possible actions. According to MacCallum, “an agent, x, is free from ‘preventing conditions’, y, to do something (or to become something), z”10. Following this definition of freedom, a ‘direct measurement’ of freedom would require ‘the enumeration of individual agents’ (more or less probably) available sets of compossible actions’11. Theoretically, this would make it possible to calculate the proportion of all possible actions that one cannot perform due to preventing conditions such as ‘constraints’, ‘limitations’, or ‘barriers’ – a requirement that is hardly fulfilled in reality and for which some proxies are consequently needed.

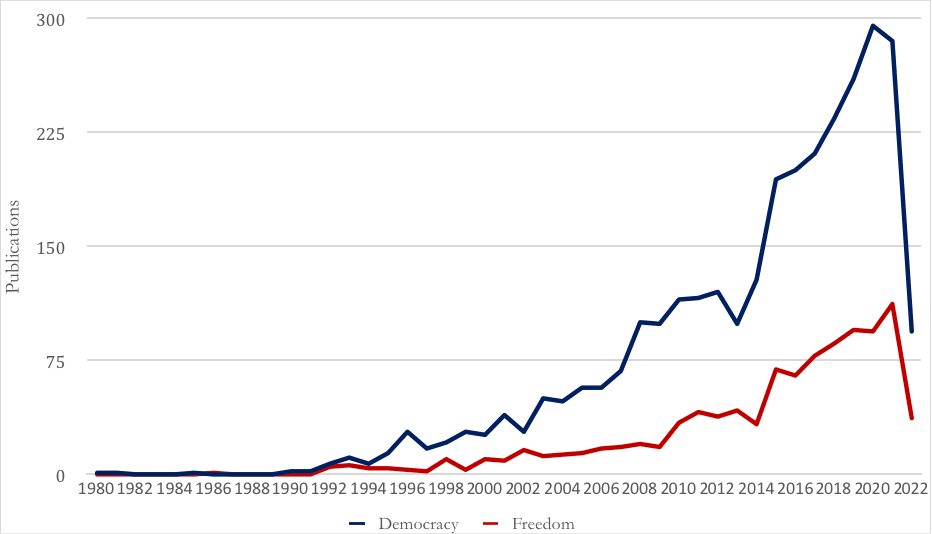

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of scientific literature on measuring freedom. While numerous studies have addressed theoretical, conceptual, and methodological aspects of measuring democracy, comparatively little attention has been paid to the measurement of freedom (see Figure 1, which shows that the number of scientific publications addressing aspects of measuring freedom compared to democracy is significantly lower). Systematic efforts to measure freedom only emerged in the 1970s, most notably with Freedom House publishing its first report in 1973. Many of these efforts at measuring freedom have been seriously flawed, “blurring various definitions of freedom … confusing ‘other good things’ with freedom, using subjective rather than objective measures, and either failing to account for economic freedom or focusing exclusively on it”12. While political theorists and philosophers engaged in epistemic debates about the (theoretical) measurability of freedom, they offered little guidance on how this might be done in practice. On the other hand, those who attempted to empirically measure freedom often paid little attention to theoretical and conceptual issues, making it somewhat questionable what these “freedom” indices actually measured.

Figure 1 Academic publications on measuring democracy and freedom

Figure 1 shows annual academic publications related to the measurement of freedom and democracy from 1980 to 2022 based on Web of Science publication data (own illustration)13.

From a theoretical point of view, political theorists have mainly focused on so-called specific freedoms (a person is free to do a specific thing) rather than overall freedom (freedom tout court). While it is widely accepted that it is possible to measure specific freedoms (such as freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, media freedom etc.), there is no consensus on the question of whether such a thing as overall freedom exists, and whether it can be measured. Influential proponents of the so-called specific freedom thesis – such as Oppenheim, Kymlicka or Dworkin – have claimed that all talk of ‘increasing’, ‘expanding’, or ‘maximizing’ freedom is not fruitful … because liberty tout court does not exist (ontological version of the specific freedom thesis), cannot be ‘even roughly measurable’ (Dworkin’s epistemic version of the thesis), or is of no great importance (normative version). Benn and Peters, for example, argue that “liberty is not a commodity to be weighed and measured. I am free to do x, y, and z, but not p, q, and r – but there is no substance called ‘freedom’ of which I can therefore possess more or less”14. Kymlicka similarly claims: “The idea of freedom as such, and lesser or greater amounts of it, does no work in political argument.”15

In his seminal monograph, A Measure of Freedom, Ian Carter refutes this view, arguing that we should think of freedom both in a specific sense (the freedom to do a certain set of things) and in a nonspecific sense (freedom as a quantitative attribute in a more general sense). Building on MacCallum’s notion of freedom as the absence of preventing conditions on agents’ possible actions, Carter argues that an empirical analysis of the state of overall freedom is doable and provides added value to political discourse as well as academic debates. While he considers measuring freedom to be theoretically possible, he acknowledges that practical problems may arise in collecting the necessary data and aggregating it into a freedom score.

Regardless of which philosophical viewpoint one takes, there is evidently a gap between the extensive theoretical discussion on the possibility of measuring freedom and the sparse empirical work on actually measuring freedom tout court. While “scholars tackling the issue of freedom are mostly interested in theoretical approaches [they] do not construct their theories or ideas with regard to empirical conditions”16. It seems almost paradoxically, the more political theorists have sought to define and conceptualise freedom, the more positivist political scientists have shied away from operationalising and measuring it. Nevertheless, various efforts have been made, with ‘Freedom in the World’ (Freedom House), the ‘Legatum Prosperity Index’ (Legatum Institute), and the ‘Human Freedom Index’ (Cato and Fraser Institute) being probably the most well-known cross-country ‘freedom’ indices.

Freedom House’s ‘Freedom in the World’ index is probably the most widely read and cited report of its kind, tracking global trends since 1973. It is a composite measure consisting of two sub-components, political rights and civil liberties. While political rights cover issues related to electoral processes, political participation and pluralism, as well as the functioning of government, civil liberties pertain to freedom of expression and belief, rights of association and organisation, personal autonomy, and the rule of law. Although Freedom House's freedom index had long been the benchmark for cross-country freedom/democracy comparisons, it has faced several criticisms. For example, critics pointed to the limited scope of the index, which neglects, for example, economic freedom17, questioned the objectivity and validity of the measurement, and argued that the index had an inherent Western bias with criteria and standards being strongly influenced by Western views on democracy and freedom18. Yet others raised concerns about the simplified categorization of countries into “free”, “partly free”, or “not free” countries, which may not fully capture the complexities related to the evolving nature of freedom and democracy.

However, what appears to be even more problematic than this simplification, by labelling countries as "free" or "not free", the ‘Freedom in the World’ index conceals its most serious deficiency, namely that it is much more a democracy rather than a freedom index. As McMahon argues, “Freedom House simply seems to assume the identity between freedom and democracy.”19 Landman and Hausermann go even further in their critique, pointing out that “the index by Freedom House has been used as a tool for measuring democracy, good governance, and human rights, thus producing a conceptual stretching which is a major cause of ‘losses in connotative precision’: in short, an instrument used to measure everything, in the end, is not able to discriminate against anything.”20 An example will illustrate this problem: If democratic structures (free and fair elections, peaceful change of government after elections, etc.) are adopted as measures of political freedom, it is no longer possible to distinguish between the effects of democracy and freedom, as one is by definition an inherent part of the other.21 Despite these criticisms, the ‘Freedom in the World’ index is a valuable resource due to its long-standing history and global coverage, which allows for comparisons over time and across countries or regions. For this reason – and although we acknowledge its limitations – we have included some selected graphs from this freedom index in the next section of this conference outlet, which can serve as an impetus for discussion in the respective panels.

One index that at least partially remedies some of these problems is the ‘Human Freedom Index’ (HFI), co-published by the Fraser and Cato Institute. Covering 98 per cent of the world’s population and including both economic freedoms and civil liberties, the HFI claims to be the most comprehensive freedom index. Based on a negative definition of freedom, the index includes 82 different indicators (40 variables on personal freedom and 42 variables on economic freedom) and a ‘gender legal rights adjustment’ to capture the extent to which women have the same level of economic freedom as men. As one of the few attempts to integrate both economic and personal freedoms, it offers intriguing insights. For example, while Sweden and Norway ranked first and fifth in personal freedom in 2019, they tied for 37th in economic freedom in 2019. In contrast, Singapore (which came second in economic freedom) scored rather poorly in personal freedom, ranking only 88th. Certainly, there are various difficulties here too, especially when it comes to weighing up the different components of freedom. How important are specific personal freedoms compared to indicators of economic freedom? Is a person A, who is in a position to trade relatively freely, has good purchasing power and is comparatively well off economically, freer than person B, who lives in a poorer country where hardly any trade is possible, but who, in contrast to A, can express their opinion freely? Can one objectively outweigh the other, or is this not an inherently subjective assessment that varies from person to person and from context to context? It is beyond the scope of this essay to address these normative issues. However, they highlight some key problems with current freedom indices, which often make many implicit assumptions – for example, that different indicators have a similar weight on an individual’s overall freedom.

This short essay is by no means meant to suggest that measuring freedom would be easy, quite the contrary. Still, I believe that paying more attention to the empirical measurement of freedom would be of great academic and political added value. For too long, political theorists and positivist social scientists have sought to approach the issue of freedom independently from each other and have adopted the stance that others’ subject areas are none of their business. Theorists have referred to the theoretical nature of their work, thus absolving themselves from formulating a realistic theory that would present specific indicators and, even more crucially, their interaction and aggregation to make freedom tout court measurable. Meanwhile, empiricists have – in the face of theorists’ definitional disagreement about freedom – begun to conflate several ‘good things’ (democracy, good governance, well-being) with freedom. Ultimately, there is a need for productive collaboration between these two professions to construct objective, reliable, and valid measurements of overall freedom. Only then can we one day really say when and why freedom is ‘in some places more’ and ‘in some places less’.

Josef Lolacher is a research associate of the Dahrendorf Programme at St Antony’s College, Oxford, and a DPhil student in Political Science at the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford.

1. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, (London: Penguin, 1985 [1651]), p. 271.

2. Ian Carter, A Measure of Freedom, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 1.

3. Roger Scruton, The Meaning of Conservatism, (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980), p. 19.

4. Bryan Magee, ‘New World Symphony’, The Guardian, 22 September 1990, cited in Carter, A Measure of Freedom, p. 1.

5. Ibid.

6. Christopher Caudwell, The Concept of Freedom, (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1965), p. 74.

7. John Sommerville, ‘Toward a Consistent Definition of Freedom and its Relation to Value’, in C.J. Friedrich (ed.), Liberty, (New York: Atherton Press, 1962), p. 300.

8. Friedrich von Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1944), p. 76.

9. Carter, A Measure of Freedom, p. 3.

10. According to MacCallum, it is these three key variables of the triadic relationship —actors, preventing conditions and action— over which the various definitions of freedom differ and how the definitional disagreements between can be restructured (see Olivier de France’s essay in this conference booklet). Evidently, these varying views also have different implications for the empirical measurement of freedom. For example, what counts as a preventing condition? Does an obstacle have to make an action physically impossible in order to be considered a preventing condition and thus a case of limited freedom or do threats count too? Can a person be unfree because they suffer from “internal” constraints? And, do constraints on freedom have to be obstacles imposed by humans, or do natural obstacles also count? This shows that questions of the concept of freedom and the measurement of freedom are closely interwoven.

11. Carter, A Measure of Freedom, p.270.

12. Fred McMahon (ed.), Towards a Worldwide Index of Human Freedom, (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2012), v.

13. Specifically, this search includes all academic publications that contain the search terms “measur* AND democracy*” or “measur* AND (freedom OR liberty)” in their titles, abstracts or as keywords and fall into the fields of political science, economics and philosophy.

14. Stanley I. Benn & Richard S. Peters, Social Principles and the Democratic State, (London: Allen & Unwin, 1959), p. 214.

15. W. Kymlicka, Contemporary Political Philosophy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 145-51.

16. Peter Graeff, ‘Measuring Individual Freedom. Actions and Rights as Indicators of Individual Liberty’, in F. McMahon (ed.), Towards a Worldwide Index of Human Freedom, (Vancouver: Fraser Institute 2012), p.113.

17. As Eugen Richter, a leading liberal in the early 20th century, argued: “Economic freedom is not safe without political freedom and political freedom finds its safety only in economic freedom.“ Eugen Richter, Im alten Reichstag. Erinnerungen, Vol. II, (Berlin: Verlag ‘Fortschritt. Aktiengesellschaft’, 1896), p.114.

18. It is worth noting that some of these points of criticism (concerns of political and Western bias, methodological validity, data availability etc.) also apply to comparable indices.

19. Fred McMahon, ‘Human Freedom from Pericles to Measurement’, in F. McMahon (ed.), Towards a Worldwide Index of Human Freedom, (Vancouver: Fraser Institute 2012), p.41.

20. cited in Diego Giannone, ‘Political and ideological aspects in the measurement of democracy: the Freedom House case’, Democratization, 17(1), 2010, p. 69.

21. For this point see Graeff, Measuring Individual Freedom, p.115.